There are outstanding issues we have now with the block protocol:

Note: I am assuming 64-bit guest/host - as the size’s of the structures change on 32-bit.

A) Segment size is limited to 11 pages. It means we can at most squeeze in 44kB per request. The ring can hold 32 (next power of two below 36) requests, meaning we can do 1.4M of outstanding requests. DONE by Roger

B). Producer and consumer index is on the same cache line. In present hardware that means the reader and writer will compete for the same cacheline causing a ping-pong between sockets.

C). The requests and responses are on the same ring. This again causes the ping-pong between sockets as the ownership of the cache line will shift between sockets.

D). Cache alignment. Currently the protocol is 16-bit aligned. This is awkward as the request and responses sometimes fit within a cacheline or sometimes straddle them.

E). Interrupt mitigation. We are currently doing a kick whenever we are done “processing” the

ring. There are better ways to do this - and we could use existing network interrupt mitigation techniques to make the code poll when there is a lot of data.

F). Latency. The processing of the request limits us to only do 44kB - which means that a 1MB chunk of data - which on contemporary devices would only use I/O request - would be split up in multiple ‘requests’ inadvertently delaying the processing of said block.

G) Future extensions. DIF/DIX for integrity. There might be other in the future and it would be good to leave space for extra flags TBD.

H). Separate the response and request rings. The current implementation has one thread for one block ring. There is no reason why there could not be two threads - one for responses and one for requests - and especially if they are scheduled on different CPUs. Furthermore this could also be split in multi-queues - so two queues (response and request) on each vCPU.

See http://kernel.dk/systor13-final18.pdf and https://lwn.net/Articles/552904/

ARIANNA is looking at this

I). We waste a lot of space on the ring - as we use the ring for both requests and responses. The response structure needs to occupy the same amount of space as the request structure (112 bytes). If the request structure is expanded to be able to fit more segments (say the ‘struct blkif_sring_entry is expanded to ~1500 bytes) that still requires us to have a matching size response structure. We do not need to use that much space for one response. Having a separate response ring would simplify the structures.

J). 32 bit vs 64 bit. Right now the size of the request structure is 112 bytes under 64-bit guest and 102 bytes under 32-bit guest. It is confusing and furthermore requires the host to do extra accounting and processing.

T

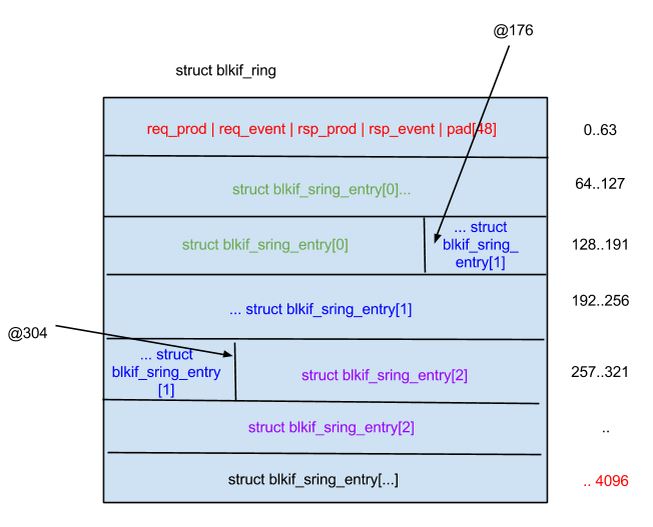

The crude drawing displays memory that the ring occupies in offset of 64 bytes (cache line). Of course future CPUs could have different cache lines (say 32 bytes?)- which would skew this drawing. A 32-bit ring is a bit different as the ‘struct blkif_sring_entry’ is of 102 bytes.

The A) has two solutions to this (look at http://comments.gmane.org/gmane.comp.emulators.xen.devel/140406 for details). One proposed by Justin from Spectralogic has to negotiate the segment size. This means that the ‘struct blkif_sring_entry’ is now a variable size. It can expand from 112 bytes (cover 11 pages of data - 44kB) to 1580 bytes (256 pages of data - so 1MB). It is a simple extension by just making the array in the request expand from 11 to a variable size negotiated.

The math is as follow.

struct blkif_request_segment {

uint32 grant; // 4 bytes

uint8_t first_sect, last_sect;// 1, 1 = 6 bytes

}(6 bytes for each segment) - the above structure is in an array of size 11 in the request. The ‘struct blkif_sring_entry’ is 112 bytes. The change is to expand the array - in this example we would tack on 245 extra ‘struct blkif_request_segment’ - 245*6 + 112 = 1582. If we were to use 36 requests (so 1582*36 + 64) we would use 57016 bytes (14 pages). This extension still limits the number of segments per request to 255 (as the total number must be specified in the request, which only has an 8-bit field for that purpose).

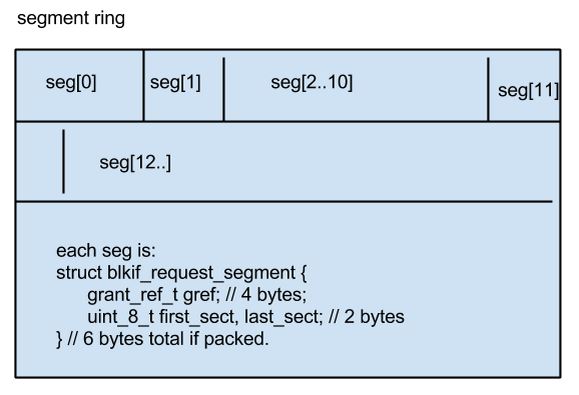

The other solution (from Intel - Ronghui) was to create one extra ring that only has the ‘struct blkif_request_segment’ in them. The ‘struct blkif_request’ would be changed to have an index in said ‘segment ring’. There is only one segment ring. This means that the size of the initial ring is still the same. The requests would point to the segment and enumerate out how many of the indexes it wants to use. The limit is of course the size of the segment. If one assumes a one-page segment this means we can in one request cover ~4MB. The math is as follow:

First request uses the half of the segment ring - so index 0 up to 341 (out of 682). Each entry in the segment ring is a ‘struct blkif_request_segment’ so it occupies 6 bytes. The other requests on the ring (so there are 35 left) can use either the remaining 341 indexes of the sgement ring or use the old style request. The old style request can address use up to 44kB. For example:

sring[0]->[uses 0->341 indexes in the segment ring] = 342*4096 = 1400832

sring[1]->[use sthe old style request] = 11*4096 = 45056

sring[2]->[uses 342->682 indexes in the segment ring] = 1392640

sring[3..32] -> [uses the old style request] = 29*4096*11 = 1306624Total: 4145152 bytes

Naturally this could be extended to have a bigger segment ring to cover more.

The problem with this extension is that we use 6 bytes and end up straddling a cache line. Using 8 bytes will fix the cache straddling. This would mean fitting only 512 segments per page.

There is yet another mechanism that could be employed - and it borrows from VirtIO protocol. And that is the ‘indirect descriptors’. This very similar to what Intel suggests, but with a twist.

We could provide a new BLKIF_OP (say BLKIF_OP_INDIRECT), and the ‘struct blkif_sring’ (each entry can be up to 112 bytes if needed - so the old style request would fit). It would look like:

/* so 64 bytes under 64-bit. If necessary, the array (seg) can be expanded to fit 11 segments as the old style request did */

struct blkif_request_indirect {

uint8_t op; /* BLKIF_OP_* (usually READ or WRITE */ // 1

blkif_vdev_t handle; /* only for read/write requests */ // 2

#ifdef CONFIG_X86_64

uint32_t _pad1; /* offsetof(blkif_request,u.rw.id) == 8 */ // 2

#endif

uint64_t id; /* private guest value, echoed in resp */

grant_ref_t gref; /* reference to indirect buffer frame if used*/

struct blkif_request_segment_aligned seg[4]; // each is 8 bytes

} __attribute__((__packed__));

struct blkif_request {

uint8_t operation; /* BLKIF_OP_??? */

union {

struct blkif_request_rw rw;

struct blkif_request_indirect indirect;

… other ..

} u;

} __attribute__((__packed__));The ‘operation’ would be BLKIF_OP_INDIRECT. The read/write/discard, etc operation would now be in indirect.op. The indirect.gref points to a page that is filled with:

struct blkif_request_indirect_entry {

blkif_sector_t sector_number;

struct blkif_request_segment seg;

} __attribute__((__packed__));

// 16 bytes, so we can fit in a page 256 of these structures.This means that with the existing 36 slots in the ring (single page) we can cover:

32 slots * each blkif_request_indirect covers: 256 * 4096 ~= 32M. If we don’t want to use indirect descriptor we can still use up to 4 pages of the request (as it has enough space to contain four segments and the structure will still be cache-aligned).

B). Both the producer (req_* and rsp_*) values are in the same cache-line. This means that we end up with the same cacheline being modified by two different guests. Depending on the architecture and placement of the guest this could be bad - as each logical CPU would try to write and read from the same cache-line. A mechanism where the req_* and rsp_ values are separated and on a different cache line could be used. The value of the correct cache-line and alignment could be negotiated via XenBus - in case future technologies start using 128 bytes for cache or such. Or the the producer and consumer indexes are in separate rings. Meaning we have a ‘request ring’ and a ‘response ring’ - and only the ‘req_prod’, ‘req_event’ are modified in the ‘request ring’. The opposite (resp_*) are only modified in the ‘response ring’.

C). Similar to B) problem but with a bigger payload. Each ‘blkif_sring_entry’ occupies 112 bytes which does not lend itself to a nice cache line size. If the indirect descriptors are to be used for everything we could ‘slim-down’ the blkif_request/response to be up-to 64 bytes. This means modifying BLKIF_MAX_SEGMENTS_PER_REQUEST to 5 as that would slim the largest of the structures to 64-bytes.

Naturally this means negotiating a new size of the structure via XenBus.

D). The first picture shows the problem. We now aligning everything on the wrong cachelines. Worst in ⅓ of the cases we straddle three cache-lines. We could negotiate a proper alignment for each request/response structure.

E). The network stack has showed that going in a polling mode does improve performance. The current mechanism of kicking the guest and or block backend is not always clear.

[TODO: Konrad to explain it in details]

F). The current block protocol for big I/Os that the backend devices can handle ends up doing extra work by splitting the I/O in smaller chunks, and then reassembling them. With the solutions outlined in A) this can be fixed. This is easily seen with 1MB I/Os. Since each request can only handle 44kB that means we have to split a 1MB I/O in 24 requests (23 * 4096 * 11 = 1081344). Then the backend ends up sending them in sector-sizes- which with contemporary devices (such as SSD) ends up with more processing. The SSDs are comfortable handling 128kB or higher I/Os in one go.

G). DIF/DIX. This a protocol to carry extra ‘checksum’ information for each I/O. The I/O can be a sector size, page-size or an I/O size (most popular are 1MB). The DIF/DIX needs 8 bytes of information for each I/O. It would be worth considering putting/reserving that amount of space in each request/response. Also putting in extra flags for future extensions would be worth it - however the author is not aware of any right now.

H). Separate response/request. Potentially even multi-queue per-VCPU queues. As v2.6.37 demonstrated, the idea of WRITE_BARRIER was flawed. There is no similar concept in the storage world were the operating system can put a food down and say: “everything before this has to be on the disk.” There are ligther versions of this - called ‘FUA’ and ‘FLUSH’. Depending on the internal implementation of the storage they are either ignored or do the right thing. The filesystems determine the viability of these flags and change writing tactics depending on this. From a protocol level, this means that the WRITE/READ/SYNC requests can be intermixed - the storage by itself determines the order of the operation. The filesystem is the one that determines whether the WRITE should be with a FLUSH to preserve some form of atomicity. This means we do not have to preserve an order of operations - so we can have multiple queues for request and responses. This has show in the network world to improve performance considerably.

I). Wastage of response/request on the same ring. Currently each response MUST occupy the same amount of space that the request occupies - as the ring can have both responses and requests. Separating the request and response ring would remove the wastage.

J). 32-bit vs 64-bit (or 102 bytes vs 112 bytes). The size of the ring entries is different if the guest is in 32-bit or 64-bit mode. Cleaning this up to be the same size would save considerable accounting that the host has to do (extra memcpy for each response/request).

转载自:block protocol