Shiro简介:Shiro是一个强大的简单易用的Java安全框架,主要用来更便捷的认证,授权,加密,会话管理。Shiro首要的和最重要的目标就是容易使用并且容易理解,通过Shiro易于理解的API,您可以快速、轻松地获得任何应用程序——从最小的移动应用程序最大的网络和企业应用程序。

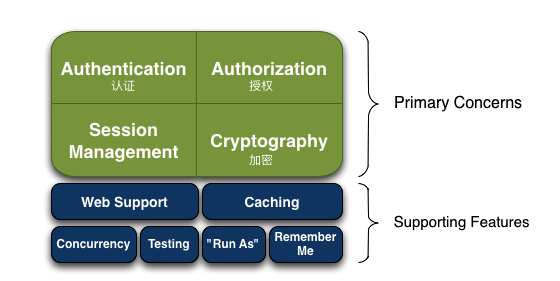

Shiro架构图

-

Authentication:身份认证/登录

-

Authorization:验证权限,即,验证某个人是否有做某件事的权限。

-

Session Management:会话管理。管理用户特定的会话,支持web,非web,ejb。

-

Cryptography: 加密,保证数据安全。

-

其他特性。

Web Support:web支持,更容易继承web应用。

扫描二维码关注公众号,回复: 2725118 查看本文章

Caching:缓存

Concurrency :多线程应用的并发验证,即如在一个线程中开启另一个线程,能把权限自动传播过去;

Testing:提供测试支持。

Run As:允许一个用户假装为另一个用户(如果他们允许)的身份进行访问;

Remember Me:记住我,即记住登录状态,一次登录后,下次再来的话不用登录了

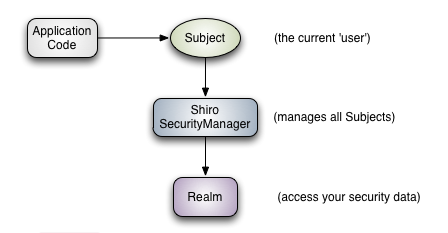

Shiro的架构有三个主要概念:Subject, SecurityManager 和 Realms。下图是一个高级的概述这些组件如何交互,下面我们将讨论每一个概念:

Subject: 当前参与应用安全部分的主角。可以是用户,可以试第三方服务,可以是cron 任务,或者任何东西。主要指一个正在与当前软件交互的东西。所有Subject都需要SecurityManager,当你与Subject进行交互,这些交互行为实际上被转换为与SecurityManager的交互。

SecurityManager:安全管理员,Shiro架构的核心,它就像Shiro内部所有原件的保护伞。然而一旦配置了SecurityManager,SecurityManager就用到的比较少,开发者大部分时间都花在Subject上面。当你与Subject进行交互的时候,实际上是SecurityManager在背后帮你举起Subject来做一些安全操作。

Realms: Realms作为Shiro和你的应用的连接桥,当需要与安全数据交互的时候,像用户账户,或者访问控制,Shiro就从一个或多个Realms中查找。Shiro提供了一些可以直接使用的Realms,如果默认的Realms不能满足你的需求,你也可以定制自己的Realms。

Shiro详细架构图

The following diagram shows Shiro’s core architectural concepts followed by short summaries of each:

Subject

Your First Apache Shiro Application

在pom.xml文件中添加Apache Shiro的依赖

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.shiro</groupId>

<artifactId>shiro-core</artifactId>

<version>1.1.0</version>

</dependency>

<!-- Shiro uses SLF4J for logging. We'll use the 'simple' binding

in this example app. See http://www.slf4j.org for more info. -->

<dependency>

<groupId>org.slf4j</groupId>

<artifactId>slf4j-simple</artifactId>

<version>1.6.1</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

The Tutorial class

We’ll be running a simple command-line application, so we’ll need to create a Java class with a public static void main(String[] args) method.

In the same directory containing your pom.xml file, create a *src/main/java sub directory. In src/main/java create a Tutorial.java file with the following contents:

src/main/java/Tutorial.java

import org.apache.shiro.SecurityUtils;

import org.apache.shiro.authc.*;

import org.apache.shiro.config.IniSecurityManagerFactory;

import org.apache.shiro.mgt.SecurityManager;

import org.apache.shiro.session.Session; import org.apache.shiro.subject.Subject; import org.apache.shiro.util.Factory; import org.slf4j.Logger; import org.slf4j.LoggerFactory; public class Tutorial { private static final transient Logger log = LoggerFactory.getLogger(Tutorial.class); public static void main(String[] args) { log.info("My First Apache Shiro Application"); System.exit(0); } } Don’t worry about the import statements for now - we’ll get to them shortly. But for now, we’ve got a typical command line program ‘shell’. All this program will do is print out the text “My First Apache Shiro Application” and exit.

Test Run

To try our Tutorial application, execute the following in a command prompt in your tutorial project’s root dirctory (e.g. shiro-tutorial), and type the following:

mvn compile exec:java

And you will see our little Tutorial ‘application’ run and exit. You should see something similar to the following (notice the bold text, indicating our output):

Run the Application

lhazlewood:~/projects/shiro-tutorial$ mvn compile exec:java

... a bunch of Maven output ...

1 [Tutorial.main()] INFO Tutorial - My First Apache Shiro Application

lhazlewood:~/projects/shiro-tutorial\$

We’ve verified the application runs successfully - now let’s enable Apache Shiro. As we continue with the tutorial, you can run mvn compile exec:java after each time we add some more code to see the results of our changes.

Enable Shiro

The first thing to understand in enabling Shiro in an application is that almost everything in Shiro is related to a central/core component called the SecurityManager. For those familiar with Java security, this is Shiro’s notion of a SecurityManager - it is NOT the same thing as the java.lang.SecurityManager.

While we will cover Shiro’s design in detail in the Architecture chapter, it is good enough for now to know that the Shiro SecurityManager is the core of a Shiro environment for an application and one SecurityManager must exist per application. So, the first thing we must do in our Tutorial application is set-up the SecurityManager instance.

Configuration

While we could instantiate a SecurityManager class directly, Shiro’s SecurityManager implementations have enough configuration options and internal components that make this a pain to do in Java source code - it would be much easier to configure the SecurityManager with a flexible text-based configuration format.

To that end, Shiro provides a default ‘common denominator’ solution via text-based INI configuration. People are pretty tired of using bulky XML files these days, and INI is easy to read, simple to use, and requires very few dependencies. You’ll also see later that with a simple understanding of object graph navigation, INI can be used effectively to configure simple object graphs like the SecurityManager.

Shiro's SecurityManager implementations and all supporting components are all JavaBeans compatible. This allows Shiro to be configured with practically any configuration format such as XML (Spring, JBoss, Guice, etc), YAML, JSON, Groovy Builder markup, and more. INI is just Shiro's 'common denominator' format that allows configuration in any environment in case other options are not available.

shiro.ini

So we’ll use an INI file to configure the Shiro SecurityManager for this simple application. First, create a src/main/resources directory starting in the same directory where the pom.xml is. Then create a shiro.ini file in that new directory with the following contents:

src/main/resources/shiro.ini

# =============================================================================

# Tutorial INI configuration

#

# Usernames/passwords are based on the classic Mel Brooks' film "Spaceballs" :)

# ============================================================================= # ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- # Users and their (optional) assigned roles # username = password, role1, role2, ..., roleN # ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- [users] root = secret, admin guest = guest, guest presidentskroob = 12345, president darkhelmet = ludicrousspeed, darklord, schwartz lonestarr = vespa, goodguy, schwartz # ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- # Roles with assigned permissions # roleName = perm1, perm2, ..., permN # ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- [roles] admin = * schwartz = lightsaber:* goodguy = winnebago:drive:eagle5 As you see, this configuration basically sets up a small set of static user accounts, good enough for our first application. In later chapters, you will see how we can use more complex User data sources like relational databases, LDAP an ActiveDirectory, and more.

Referencing the Configuration

Now that we have an INI file defined, we can create the SecurityManager instance in our Tutorial application class. Change the main method to reflect the following updates:

public static void main(String[] args) { log.info("My First Apache Shiro Application"); //1. Factory<SecurityManager> factory = new IniSecurityManagerFactory("classpath:shiro.ini"); //2. SecurityManager securityManager = factory.getInstance(); //3. SecurityUtils.setSecurityManager(securityManager); System.exit(0); } And there we go - Shiro is enabled in our sample application after adding only 3 lines of code! How easy was that?

Feel free to run mvn compile exec:java and see that everything still runs successfully (due to Shiro’s default logging of debug or lower, you won’t see any Shiro log messages - if it starts and runs without error, then you know everything is still ok).

Here is what the above additions are doing:

-

We use Shiro’s

IniSecurityManagerFactoryimplementation to ingest ourshiro.inifile which is located at the root of the classpath. This implementation reflects Shiro’s support of the Factory Method Design Pattern. Theclasspath:prefix is an resource indicator that tells shiro where to load the ini file from (other prefixes, likeurl:andfile:are supported as well). -

The

factory.getInstance()method is called, which parses the INI file and returns aSecurityManagerinstance reflecting the configuration. -

In this simple example, we set the

SecurityManagerto be a static (memory) singleton, accessible across the JVM. Note however that this is not desireable if you will ever have more than one Shiro-enabled application in a single JVM. For this simple example, it is ok, but more sophisticated application environments will usually place theSecurityManagerin application-specific memory (such as in a web app’sServletContextor a Spring, Guice or JBoss DI container instance).

Using Shiro

Now that our SecurityManager is set-up and ready-to go, now we can start doing the things we really care about - performing security operations.

When securing our applications, probably the most relevant questions we ask ourselves are “Who is the current user?” or “Is the current user allowed to do X”? It is common to ask these questions as we’re writing code or designing user interfaces: applications are usually built based on user stories, and you want functionality represented (and secured) based on a per-user basis. So, the most natural way for us to think about security in our application is based on the current user. Shiro’s API fundamentally represents the notion of ‘the current user’ with its Subject concept.

In almost all environments, you can obtain the currently executing user via the following call:

Subject currentUser = SecurityUtils.getSubject();

Using SecurityUtils.getSubject(), we can obtain the currently executing Subject. Subject is a security term that basically means “a security-specific view of the currently executing user”. It is not called a ‘User’ because the word ‘User’ is usually associated with a human being. In the security world, the term ‘Subject’ can mean a human being, but also a 3rd party process, cron job, daemon account, or anything similar. It simply means ‘the thing that is currently interacting with the software’. For most intents and purposes though, you can think of the Subject as Shiro’s ‘User’ concept.

The getSubject() call in a standalone application might return a Subject based on user data in an application-specific location, and in a server environment (e.g. web app), it acquires the Subject based on user data associated with current thread or incoming request.

Now that you have a Subject, what can you do with it?

If you want to make things available to the user during their current session with the application, you can get their session:

Session session = currentUser.getSession();

session.setAttribute( "someKey", "aValue" );

The Session is a Shiro-specific instance that provides most of what you’re used to with regular HttpSessions but with some extra goodies and one big difference: it does not require an HTTP environment!

If deploying inside a web application, by default the Session will be HttpSession based. But, in a non-web environment, like this simple tutorial application, Shiro will automatically use its Enterprise Session Management by default. This means you get to use the same API in your applications, in any tier, regardless of deployment environment! This opens a whole new world of applications since any application requiring sessions does not need to be forced to use the HttpSession or EJB Stateful Session Beans. And, any client technology can now share session data.

So now you can acquire a Subject and their Session. What about the really useful stuff like checking if they are allowed to do things, like checking against roles and permissions?

Well, we can only do those checks for a known user. Our Subject instance above represents the current user, but who is the current user? Well, they’re anonymous - that is, until they log in at least once. So, let’s do that:

if ( !currentUser.isAuthenticated() ) {

//collect user principals and credentials in a gui specific manner

//such as username/password html form, X509 certificate, OpenID, etc.

//We'll use the username/password example here since it is the most common.

UsernamePasswordToken token = new UsernamePasswordToken("lonestarr", "vespa"); //this is all you have to do to support 'remember me' (no config - built in!): token.setRememberMe(true); currentUser.login(token); } That’s it! It couldn’t be easier.

But what if their login attempt fails? You can catch all sorts of specific exceptions that tell you exactly what happened and allows you to handle and react accordingly:

try {

currentUser.login( token );

//if no exception, that's it, we're done!

} catch ( UnknownAccountException uae ) {

//username wasn't in the system, show them an error message?

} catch ( IncorrectCredentialsException ice ) { //password didn't match, try again? } catch ( LockedAccountException lae ) { //account for that username is locked - can't login. Show them a message? } ... more types exceptions to check if you want ... } catch ( AuthenticationException ae ) { //unexpected condition - error? } There are many different types of exceptions you can check, or throw your own for custom conditions Shiro might not account for. See the AuthenticationException JavaDoc for more.

Security best practice is to give generic login failure messages to users because you do not want to aid an attacker trying to break into your system.

Ok, so by now, we have a logged in user. What else can we do?

Let’s say who they are:

//print their identifying principal (in this case, a username):

log.info( "User [" + currentUser.getPrincipal() + "] logged in successfully." );

We can also test to see if they have specific role or not:

if ( currentUser.hasRole( "schwartz" ) ) {

log.info("May the Schwartz be with you!" );

} else {

log.info( "Hello, mere mortal." ); } We can also see if they have a permission to act on a certain type of entity:

if ( currentUser.isPermitted( "lightsaber:weild" ) ) {

log.info("You may use a lightsaber ring. Use it wisely.");

} else {

log.info("Sorry, lightsaber rings are for schwartz masters only."); } Also, we can perform an extremely powerful instance-level permission check - the ability to see if the user has the ability to access a specific instance of a type:

if ( currentUser.isPermitted( "winnebago:drive:eagle5" ) ) {

log.info("You are permitted to 'drive' the 'winnebago' with license plate (id) 'eagle5'. " +

"Here are the keys - have fun!");

} else { log.info("Sorry, you aren't allowed to drive the 'eagle5' winnebago!"); } Piece of cake, right?

Finally, when the user is done using the application, they can log out:

currentUser.logout(); //removes all identifying information and invalidates their session too.

Final Tutorial class

After adding in the above code examples, here is our final Tutorial class file. Feel free to edit and play with it and change the security checks (and the INI configuration) as you like:

Final src/main/java/Tutorial.java

import org.apache.shiro.SecurityUtils;

import org.apache.shiro.authc.*;

import org.apache.shiro.config.IniSecurityManagerFactory;

import org.apache.shiro.mgt.SecurityManager;

import org.apache.shiro.session.Session; import org.apache.shiro.subject.Subject; import org.apache.shiro.util.Factory; import org.slf4j.Logger; import org.slf4j.LoggerFactory; public class Tutorial { private static final transient Logger log = LoggerFactory.getLogger(Tutorial.class); public static void main(String[] args) { log.info("My First Apache Shiro Application"); Factory<SecurityManager> factory = new IniSecurityManagerFactory("classpath:shiro.ini"); SecurityManager securityManager = factory.getInstance(); SecurityUtils.setSecurityManager(securityManager); // get the currently executing user: Subject currentUser = SecurityUtils.getSubject(); // Do some stuff with a Session (no need for a web or EJB container!!!) Session session = currentUser.getSession(); session.setAttribute("someKey", "aValue"); String value = (String) session.getAttribute("someKey"); if (value.equals("aValue")) { log.info("Retrieved the correct value! [" + value + "]"); } // let's login the current user so we can check against roles and permissions: if (!currentUser.isAuthenticated()) { UsernamePasswordToken token = new UsernamePasswordToken("lonestarr", "vespa"); token.setRememberMe(true); try { currentUser.login(token); } catch (UnknownAccountException uae) { log.info("There is no user with username of " + token.getPrincipal()); } catch (IncorrectCredentialsException ice) { log.info("Password for account " + token.getPrincipal() + " was incorrect!"); } catch (LockedAccountException lae) { log.info("The account for username " + token.getPrincipal() + " is locked. " + "Please contact your administrator to unlock it."); } // ... catch more exceptions here (maybe custom ones specific to your application? catch (AuthenticationException ae) { //unexpected condition? error? } } //say who they are: //print their identifying principal (in this case, a username): log.info("User [" + currentUser.getPrincipal() + "] logged in successfully."); //test a role: if (currentUser.hasRole("schwartz")) { log.info("May the Schwartz be with you!"); } else { log.info("Hello, mere mortal."); } //test a typed permission (not instance-level) if (currentUser.isPermitted("lightsaber:weild")) { log.info("You may use a lightsaber ring. Use it wisely."); } else { log.info("Sorry, lightsaber rings are for schwartz masters only."); } //a (very powerful) Instance Level permission: if (currentUser.isPermitted("winnebago:drive:eagle5")) { log.info("You are permitted to 'drive' the winnebago with license plate (id) 'eagle5'. " + "Here are the keys - have fun!"); } else { log.info("Sorry, you aren't allowed to drive the 'eagle5' winnebago!"); } //all done - log out! currentUser.logout(); System.exit(0); } } Summary

Hopefully this introduction tutorial helped you understand how to set-up Shiro in a basic application as well Shiro’s primary design concepts, the Subject and SecurityManager.

But this was a fairly simple application. You might have asked yourself, “What if I don’t want to use INI user accounts and instead want to connect to a more complex user data source?”

To answer that question requires a little deeper understanding of Shiro’s architecture and supporting configuration mechanisms. We’ll cover Shiro’s Architecture next.