此处的面向对象进阶是一个个小的知识点,之间没有太多关联性。

- 1. isinstance(obj,cls) 和 issubclass()

- isinstance(obj,cls):判断是是obj对象是否来自于cls这个类

class Foo: pass class Bar(Foo): pass b1=Bar() print(isinstance(b1,Bar)) # True print(isinstance(b1,Foo)) # True # b1也是Foo的实例。 print(type(b1)) # <class '__main__.Bar'>

-

- issubclass(sub,super):检查sub类是否是 super 类的派生类

class Foo: pass # Bar继承Foo class Bar(Foo): pass # 判断Bar是否继承Foo print(issubclass(Bar, Foo)) # True

- 2. __getattribute__

class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattr__(self, item): print('执行的是我') # return self.__dict__[item] f1=Foo(10) print(f1.x) f1.xxxxxx #不存在的属性访问,触发__getattr__ 回顾__getattr__

(1)不管属性是否存在,__getattribute__都会执行

# 不管属性是否存在,__getattribute__都会执行 class Foo: def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattribute__(self, item): print('不管属性是否存在,我都会执行') f1=Foo(10) # 1. f1有x属性,触发 __getattribute__(self, item): print(f1.x) # 执行的是getattribute # 2. f1没有xxxx属性,也是触发__getattribute__ print(f1.xxxxx) # 执行的是getattribute

(2)如果__getattribute__ 和 __getattr__同时存在时,只会执行__getattribute__,除非__getattribute__在执行过程中抛出异常AttributeError

class Foo: y = 1 def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattr__(self, item): return '执行的是getattr' # return self.__dict__[item] def __getattribute__(self, item): print('执行的是getattribute') raise AttributeError('抛出异常了') # 抛出的异常必须是AttributeError,不能是其他异常 f1=Foo(10) # 1. f1有y属性,触发 __getattribute__(self, item): print(f1.y) # 执行的是getattribute # 执行的是getattr ''' 问题:为什么y属性存在,也执行了__getattr__,因为第一步先执行__getattribute__的时候,里面有抛出属性异常, 只要__getattribute__里有抛出属性异常,就会去执行__getattr__ ''' # 2. f1没有xxxx属性,也是触发__getattribute__ print(f1.xxxxx) # 执行的是getattribute # 执行的是getattribute # 执行的是getattr

'''

问题:xxxx属性是不存在的,为什么没有抛出异常呢?

解答:

这就是__getattr__的功能。

1. 如果只有__getattribute__,那 xxxx属性不存在时,就会直接抛出异常了(见下面的示例),程序崩掉。

2. 当__getattr__ 和 __getattribute__同时存在时,__getattr__就是在时时刻刻监听着__getattribute__是否抛出异常,如果抛出异常了,

那__getattr__就自动接收,然后执行__getattr__的逻辑,而不至于让程序崩掉。

'''

'''

__getattribute__是系统内置的方法,如果你没有写到程序里,其实系统也会自动执行,如果没异常,你是看不出来的,如果出现异常了,就会直接报错,程序崩掉了。

'''

class Foo: y = 1 def __init__(self,x): self.x=x def __getattribute__(self, item): print('执行的是getattribute') raise AttributeError('抛出异常了') # 抛出的异常必须是AttributeError,不能是其他异常 f1=Foo(10) print(f1.xxxxx) # AttributeError: 抛出异常了

- 3. item系列

__getitem__:根据key,查询值

__setitem__:新增或修改字典的属性

__delitem__:根据key删除字典的属性

class Foo: def __getitem__(self, item): print('执行getitem',item) return self.__dict__[item] def __setitem__(self, key, value): print('执行setitem') self.__dict__[key]=value def __delitem__(self, key): print('执行delitem') self.__dict__.pop(key) f1=Foo() print(f1.__dict__) # {} f1['name']='egon'#--->setitem--------->f1.__dict__['name']='egon' # 执行setitem f1['age']=18 # 执行setitem print('===>',f1.__dict__) # ===> {'name': 'egon', 'age': 18} del f1['name'] # 执行delitem print(f1.__dict__) # {'age': 18} print(f1['age']) # 执行getitem age # 18 # item系列都是跟字典相关的,操作要以 []的方式操作 # attr系统都是跟属性相关的,操作要以 .的方式操作

- 4. __str__,__repr__,__format__

改变对象的字符串显示__str__,__repr__:

(1) __str__:是print的时候用的

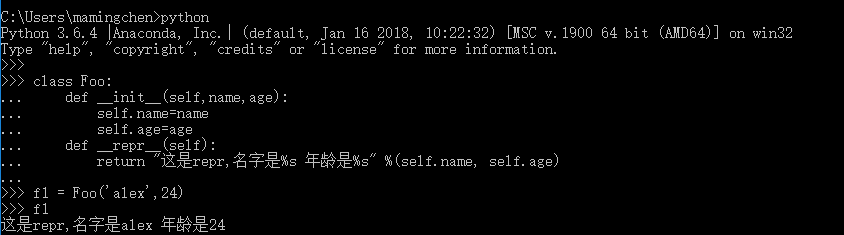

(2)__repr__:是在解释器里用的

自定制格式化字符串__format__

class Foo: def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age f1=Foo('egon',18) print(f1) #实际上触发的是str(f1)--->而str(f1)触发的则是f1.__str__() # 这种方式你除了能得到下面的信息之外,什么都不知道,对你的实际意义也不大 # <__main__.Foo object at 0x010D9350>

# class Foo: def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age # 定制了__str__方法,当调用到str(f1)是,实际还是调用该的f1.__str__(),只不过是执行的是定制的方法 def __str__(self): # 这个方法必须有return,这是规定 return '名字是%s 年龄是%s' %(self.name,self.age) f1=Foo('egon',18) print(f1) # 名字是egon 年龄是18 ''' 普及print()背后的执行逻辑: 1. print执行时,调用的是str(f1) 2. 而str(f1),在Python内部实际是调用的f1.__str__()方法 '''

class Foo: def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age def __repr__(self): return "这是repr,名字是%s 年龄是%s" %(self.name, self.age) f1=Foo('egon',18) print(f1) # 这是repr,名字是egon 年龄是18

class Foo: def __init__(self,name,age): self.name=name self.age=age # 定制了__str__方法,当调用到str(f1)是,实际还是调用该的f1.__str__(),只不过是执行的是定制的方法 def __str__(self): # 这个方法必须有return,这是规定 return '名字是%s 年龄是%s' %(self.name,self.age) def __repr__(self): return "这是repr,名字是%s 年龄是%s" %(self.name, self.age) f1=Foo('egon',18) print(f1) # 名字是egon 年龄是18 ''' 1. 当__str__ 和 __repr__共存时,print(obj)本质就是去找str()--->obj.__str__(); 2. 结合前面两个示例,如果没有找到obj.__str__方法,就会去找obj.__repr__方法替代 '''

小总结:

1. str函数或者print函数,实际触发的是obj.__str__()

2. repr或者交互式解释器, 实际触发的是obj.__repr__()

3. 如果__str__没有被定义,那么就会使用__repr__来代替输出

注意:这俩方法的返回值必须是字符串,否则抛出异常

st = "{},{},{}".format("dog","cat","pig") print(st) # dog,cat,pig

class Date: def __init__(self,year,mon,day): self.year=year self.mon=mon self.day=day d1=Date(2018,7,21) x='{0.year}{0.mon}{0.day}'.format(d1) y='{0.year}:{0.mon}:{0.day}'.format(d1) z='{0.mon}-{0.day}-{0.year}'.format(d1) print(x) print(y) print(z) # 2018721 # 2018:7:21 # 7-21-2018 ''' 这种方法,看着就比较笨,如果时间格式经常变换,你就需要改代码 '''

# 定义格式的 format_dic={ 'ymd':'{0.year}{0.mon}{0.day}', 'm-d-y':'{0.mon}-{0.day}-{0.year}', 'y:m:d':'{0.year}:{0.mon}:{0.day}' } class Date: def __init__(self,year,mon,day): self.year=year self.mon=mon self.day=day def __format__(self, format_spec): print('我执行啦') print('--->',format_spec) # 如果没有指定的format_spec 或者 format_spec 不在format_dic字典里,就用默认的ymd格式 if not format_spec or format_spec not in format_dic: format_spec='ymd' fm=format_dic[format_spec] return fm.format(self) d1=Date(2016,12,26) # format(d1) #d1.__format__() # print(format(d1)) print(format(d1,'ymd')) print(format(d1,'y:m:d')) # 可以随便输入格式 print(format(d1,'m-d-y')) print(format(d1,'m-d:y')) print('===========>',format(d1,'asdfasasd'))

- 5.__slots__

1.__slots__是什么?

是一个类变量,变量值可以是列表,元祖,或者可迭代对象,也可以是一个字符串(意味着所有实例只有一个数据属性)

2.引子:使用点来访问属性本质就是在访问类或者对象的__dict__属性字典

(类的字典是共享的,目的是为了省内存,如果类不不共享的话,意味着每个实例都需要写自己的字典;而每个实例的是独立的)

3.为何使用__slots__?

(1)字典会占用大量内存,如果你有一个属性很少的类,但是有很多实例,为了节省内存可以使用__slots__取代实例的__dict__

(2)当你定义__slots__后,__slots__就会为实例使用一种更加紧凑的内部表示。

(4)实例通过一个很小的固定大小的数组来构建,而不是为每个实例定义一个字典,这跟元组或列表很类似。

(3)在__slots__中列出的属性名在内部被映射到这个数组的指定小标上。使用__slots__一个不好的地方就是我们不能再给实例添加新的属性了,

只能使用在__slots__中定义的那些属性名。

4.注意事项:

(1)__slots__的很多特性都依赖于普通的基于字典的实现。

(2)另外,定义了__slots__后的类不再 支持一些普通类特性了,比如多继承。

(3)大多数情况下,你应该只在那些经常被使用到 的用作数据结构的类上定义__slots__比如在程序中需要创建某个类的几百万个实例对象 。

(4)关于__slots__的一个常见误区是它可以作为一个封装工具来防止用户给实例增加新的属性。尽管使用__slots__可以达到这样的目的,但是这个并不是它的初衷。

更多的是用来作为一个内存优化工具。

class Foo: # 1. __slost__:是定义在类当中的类变量。列表,元组,字符串都可以的 # __slots__只是定义了key,具体的值没有定义,需要实例化后进行定义 # 所以初始的值就是None。{'name':None,'age':None} __slots__=['name','age'] # __slots__='name' #{'name':None,'age':None} f1=Foo() # 2. 实例化后,实例可以定义__slots__属性已经提供的name, age。 f1.name='egon' f1.age=18 print(f1.name) # egon print(f1.age) # 18 # 3. 定义之后,限制了实例继续创建其他属性。也就是说,而已经无法定义__slots__未提供的属性 f1.gender = 'male' # AttributeError: 'Foo' object has no attribute 'gender' # 4. 定义之后,由这个类产生的实例,不再具有__dict__属性 print(f1.__dict__) # AttributeError: 'Foo' object has no attribute '__dict__' # 5. 查看Foo类和f1实例有哪些属性 print(Foo.__slots__) print(f1.__slots__) # ['name', 'age'] # ['name', 'age'] # 6.可以修改__slots__存在的属性的值 f1.age=17 print(f1.age) # 17

class Foo: __slots__=['name','age'] f1=Foo() f1.name='alex' f1.age=18 print(f1.__slots__) f2=Foo() f2.name='egon' f2.age=19 print(f2.__slots__) print(Foo.__dict__) #f1与f2都没有属性字典__dict__了,统一归__slots__管,节省内存 刨根问底

- 6.__doc__: 文档描述符

class Foo: '我是描述信息' pass print(Foo.__doc__) # 我是描述信息

__doc__属性的特殊之处在于,它是无法继承的

class Foo: '我是描述信息' pass class Bar(Foo): pass print(Foo.__doc__) # 我是描述信息 print(Bar.__doc__) #该属性无法继承给子类 # None

- 7. __module__和__class__

__module__ 表示当前操作的对象在那个模块

__class__ 表示当前操作的对象的类是什么

1 class C: 2 3 def __init__(self): 4 self.name = ‘1234'

from lib.aa import C # 从lib.aa 导入C模块 # 实例化 obj = C() print(obj.name) # 1234 print(obj.__module__) # 输出 lib.aa,即:输出模块 print(obj.__class__) # 输出 lib.aa.C,即:输出类

- 8.__del__:析构方法

析构方法,当对象在内存中被释放时,自动触发执行。

注:

(1)如果产生的对象仅仅只是python程序级别的(用户级),那么无需定义__del__;

(2)如果产生的对象的同时还会向操作系统发起系统调用,即一个对象有用户级与内核级两种资源,比如(打开一个文件,创建一个数据库链接),则必须在清除对象的同时回收系统资源,这就用到了__del__

class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __del__(self): print('析构函数执行啦') f1=Foo('lex') # 1. __del__只在实例被删除的时候才会触发__del__ # del f1 # 析构函数执行啦 # ---------------------> # 2. 直接执行print语句 print('--------------------->') # ---------------------> # 析构函数执行啦 # 3.删除实例的属性不会触发__del__ del f1.name print('--------------------->') # ---------------------> # 析构函数执行啦 ''' 为什么 1 会先执行__del__,而 2 和 3都是后执行__del__? (1) __del__只在实例被删除的时候才会触发__del__, 所以 1 会触发 __del__执行 (2) 3 删除实例的属性不会触发__del__, 2 和 3 之所以执行__del__, 是程序运行完毕会自动回收内存,才触发__del__ '''

典型的应用场景:

创建数据库类,用该类实例化出数据库链接对象,对象本身是存放于用户空间内存中,而链接则是由操作系统管理的,存放于内核空间内存中

当程序结束时,python只会回收自己的内存空间,即用户态内存,而操作系统的资源则没有被回收,这就需要我们定制__del__,在对象被删除前向操作系统发起关闭数据库链接的系统调用,回收资源

这与文件处理是一个道理:

f=open('a.txt') #做了两件事,在用户空间拿到一个f变量,在操作系统内核空间打开一个文件 del f #只回收用户空间的f,操作系统的文件还处于打开状态 #所以我们应该在del f之前保证f.close()执行,即便是没有del,程序执行完毕也会自动del清理资源,于是文件操作的正确用法应该是 f=open('a.txt') 读写... f.close() 很多情况下大家都容易忽略f.close,这就用到了with上下文管理

- 9. __call__

对象后面加括号,触发执行。

注:

(1) 构造方法的执行是由创建对象触发的,即:对象 = 类名() ;

(2) 而对于 __call__ 方法的执行是由对象后加括号触发的,即:对象() 或者 类()()

class Foo: pass f1=Foo() f1() # TypeError: 'Foo' object is not callable

class Foo: def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): print('实例执行啦 obj()') f1=Foo() # Foo()触发__call__方法,__call__方法给你返回一个实例f1 f1() # 实例执行啦 obj() # 实例f1加()调用的是f1实例的类下面的__call__方法 Foo() # Foo加()能运行,实际也是调的Foo实例所属的类 xxx下的__call__方法

- 10.__next__和__iter__实现迭代器协议

1. 迭代器协议是指:对象必须提供一个next方法,执行该方法要么返回迭代中的下一项,要么就引起一个Stopiteration异常,以终止迭代(只能往后走,不能往前退)

2.可迭代对象:实现了迭代器协议的对象(如何实现,对象内部定义一个__iter__()方法)

3.协议是一种约定,可迭代对象实现了迭代器协议,Python的内部工具(如for循环,sum, min,max函数等)使用迭代器协议访问对象。

4. python中强大的for循环的本质:循环所有对象,全都是使用迭代器协议。

class Foo: def __init__(self,n): self.n=n # 怎么样把一个对象变成一个可迭代对象呢?迭代器协议规定必须具有: # 1. 必须在类里有一个__iter__方法, 才能将一个对象变成一个可迭代的对象 def __iter__(self): return self # 2. 还必须要有一个__next__方法 def __next__(self): if self.n == 13: # 3. 迭代器协议当遇到异常时可以抛出异常,终止运行 raise StopIteration('终止了') self.n+=1 return self.n '''

1 和 2 是必须同时存在的

'''

f1=Foo(10) print(f1.__next__()) # 11 print(f1.__next__()) # 12 print(next(f1)) # 13 print(next(f1)) # StopIteration: 终止了 # for 循环一个对象,是先把这个对象变成一个iter(f1) 迭代器,等同于 f1.__iter__() # for i in f1: # obj=iter(f1)------------>f1.__iter__() # print(i) #obj.__next_()

练习:迭代器协议实现斐波那契数列

斐波那契数列:后面一个数是前面两个数的和

1 1 2 3 5 8 13...

class Fib: def __init__(self): # 首先得有起始的两个值, 写死了。 self._a=1 self._b=1 def __iter__(self): return self def __next__(self): if self._a > 100: raise StopIteration('终止了') # 异常名StopIteration # 交换值的方式实现 self._a,self._b=self._b,self._a + self._b return self._a f1=Fib() print(next(f1)) print(next(f1)) print(next(f1)) print(next(f1)) print(next(f1)) print('==================================') # for 循环的,还是接着当前的next往下走 for i in f1: print(i)

- 11.描述符(__get__,__set__,__delete__)

1 描述符是什么:描述符本质就是一个新式类,在这个新式类中,至少实现了__get__(),__set__(),__delete__()中的一个,这也被称为描述符协议

__get__():调用一个属性时,触发

__set__():为一个属性赋值时,触发

__delete__():采用del删除属性时,触发

# 定义一个描述符 class Foo: #在python3中Foo是新式类,它实现了三种方法,这个类就被称作一个描述符 def __get__(self, instance, owner): pass def __set__(self, instance, value): pass def __delete__(self, instance): pass

# 描述符Foo class Foo: pass # 描述符Bar class Bar: # 表示在Bar类里,用Foo类代理了Bar类中的x属性,也就是跟x有关的属性都交给Foo去做。 # x 就是被代理属性

# 描述符必须被定义到类属性里,不能定义到构造函数里

x=Foo() def __init__(self,n): self.x=n #b1.x=10

2 描述符是干什么的:描述符的作用是用来代理另外一个类的属性的(必须把描述符定义成这个类的类属性,不能定义到构造函数中)

引子:描述符类产生的实例进行属性操作并不会触发三个方法的执行

引子:描述符类产生的实例进行属性操作并不会触发三个方法的执行

# 描述符Foo class Foo: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('===>get方法') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('===>set方法',instance,value) instance.__dict__['x']=value #b1.__dict__ def __delete__(self, instance): print('===>delete方法') # 描述符Bar class Bar: # 在何地用描述符? # [答] 定义成另外一个类的类属性 # 此处的Foo描述符被定义成了Bar这个类的类属性,并赋值给了类变量x。----这就是描述符的使用地 x=Foo() def __init__(self,n): self.x=n #b1.x=10 # 在何时用描述符? # 1. 实例化时 b1=Bar(10) # ===>set方法 <__main__.Bar object at 0x00BE2ED0> 10 # 实例化的时候,就要调用了Foo描述符的__set__方法,给实例的属性字典x set了一个值 # 看一下实例b1的字典里x的值是否set成功 print(b1.__dict__) # {'x': 10} # 2. 修改实例b1的 x属性的值时 b1.x=14 # ===>set方法 <__main__.Bar object at 0x00B52F10> 14 print(b1.__dict__) # {'x': 14} # 给实例b1的属性字典里新增一个y属性,其值为16 # 我们发现并没有调用Foo描述符?为什么? # 这是因为y不是Bar的类属性,y没有调用Foo,而是调用的Bar自己的__setattr__方法 b1.y=16 print(b1.__dict__) # {'x': 14, 'y': 16} print(Bar.__dict__) # {'__module__': '__main__', 'x': <__main__.Foo object at 0x006E51F0>, '__init__': <function Bar.__init__ at 0x006E1AE0>, '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'Bar' objects>, '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'Bar' objects>, '__doc__': None} # 3. 在删除实例b1的x属性时 del b1.x # ===>delete方法 # 打印x的值 print(b1.x) # None # 查看x是否还在b1的属性字典里,看是否删除成功 print(b1.__dict__) # {'x': 14, 'y': 16} # 为什么b1属性字典里还有x的值? ''' '''

3 描述符分两种

(1) 数据描述符:至少实现了__get__()和__set__()

class Foo: def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set') def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get')

(2) 非数据描述符:没有实现__set__()

class Foo: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get')

4 注意事项:

一 描述符本身应该定义成新式类,被代理的类也应该是新式类(描述符就是用来描述其他类的, 描述其他类的类属性的)

二 必须把描述符定义成这个类的类属性,不能定义到构造函数中(构造函数是来定义实例属性的,所以不能定义到构造函数中)

三 要严格遵循该优先级,优先级由高到底分别是

1.类属性

2.数据描述符

3.实例属性

4.非数据描述符

5.找不到的属性触发__getattr__()

#描述符Str class Str: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('Str调用') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('Str设置...') def __delete__(self, instance): print('Str删除...') class People: name=Str() def __init__(self,name,age): #name被Str类代理,age被Int类代理, self.name=name self.age=age #基于上面的演示,我们已经知道,在一个类中定义描述符它就是一个类属性,存在于类的属性字典中,而不是实例的属性字典 #那既然描述符被定义成了一个类属性,直接通过类名也一定可以调用吧,没错 People.name #恩,调用类属性name,本质就是在调用描述符Str,触发了__get__() People.name='egon' #那赋值呢,我去,并没有触发__set__() del People.name #赶紧试试del,我去,也没有触发__delete__() #结论:描述符对类没有作用-------->傻逼到家的结论 ''' 原因:描述符在使用时被定义成另外一个类的类属性,因而类属性比二次加工的描述符伪装而来的类属性有更高的优先级 People.name #恩,调用类属性name,找不到就去找描述符伪装的类属性name,触发了__get__() People.name='egon' #那赋值呢,直接赋值了一个类属性,它拥有更高的优先级,相当于覆盖了描述符,肯定不会触发描述符的__set__() del People.name #同上 ''' 类属性>数据描述符

#描述符Str class Str: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('Str调用') def __set__(self, instance, value): print('Str设置...') def __delete__(self, instance): print('Str删除...') class People: name=Str() def __init__(self,name,age): #name被Str类代理,age被Int类代理, self.name=name self.age=age p1=People('egon',18) #如果描述符是一个数据描述符(即有__get__又有__set__),那么p1.name的调用与赋值都是触发描述符的操作,于p1本身无关了,相当于覆盖了实例的属性 p1.name='egonnnnnn' p1.name print(p1.__dict__)#实例的属性字典中没有name,因为name是一个数据描述符,优先级高于实例属性,查看/赋值/删除都是跟描述符有关,与实例无关了 del p1.name

class Foo: def func(self): print('我胡汉三又回来了') f1=Foo() f1.func() #调用类的方法,也可以说是调用非数据描述符 #函数是一个非数据描述符对象(一切皆对象么) print(dir(Foo.func)) print(hasattr(Foo.func,'__set__')) print(hasattr(Foo.func,'__get__')) print(hasattr(Foo.func,'__delete__')) #有人可能会问,描述符不都是类么,函数怎么算也应该是一个对象啊,怎么就是描述符了 #笨蛋哥,描述符是类没问题,描述符在应用的时候不都是实例化成一个类属性么 #函数就是一个由非描述符类实例化得到的对象 #没错,字符串也一样 f1.func='这是实例属性啊' print(f1.func) del f1.func #删掉了非数据 f1.func()

class Foo: def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set') def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get') class Room: name=Foo() def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length #name是一个数据描述符,因为name=Foo()而Foo实现了get和set方法,因而比实例属性有更高的优先级 #对实例的属性操作,触发的都是描述符的 r1=Room('厕所',1,1) r1.name r1.name='厨房' class Foo: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get') class Room: name=Foo() def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length #name是一个非数据描述符,因为name=Foo()而Foo没有实现set方法,因而比实例属性有更低的优先级 #对实例的属性操作,触发的都是实例自己的 r1=Room('厕所',1,1) r1.name r1.name='厨房' 再次验证:实例属性>非数据描述符

class Foo: def func(self): print('我胡汉三又回来了') def __getattr__(self, item): print('找不到了当然是来找我啦',item) f1=Foo() f1.xxxxxxxxxxx

5 描述符使用

众所周知,python是弱类型语言,即参数的赋值没有类型限制,下面我们通过描述符机制来实现类型限制功能

弱类型:不用定义变量的类型就可以使用。

def test(x): print("能输入",x) test('123') # 能输入 123 test(1234) # 能输入 1234 # 输入字符串和整数,都可以正常运行,说明Python是弱类型语言,没有类型检测功能

需求:利用描述符检查输入的类型,并限制不符合期待的类型的输入

class People: def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary p1 = People('alex', 24, 25000) p2 = People( 14, 24, 25000) # p1 和 p2 name分别是字符串和整型,都可以正常传入,没有做限制 # 所以,先给name做一下类型限制

Step1:用描述符的方式给加限制,定义描述符就要考虑是定义成数据描述符还是非数据描述符。先定义成非数据描述符:

# 如果定义成非数据描述符 class Typed: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print("get方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) print("owner参数是[%s]" %owner) class People: name = Typed() # 利用描述符,就要先定义描述符 def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary p1 = People('alex', 24, 25000) p1.name = 'eggor' print(p1.__dict__) ''' 实例化的时候没有调用非数据描述法,因为:实例的优先级高于非数据描述法, 所以实例化的时候,就直接调用People自己的构造方法了。而我们的需求是要在实例化或者赋值的时候要检测name的类型,而直接调用People自己的构造方法,

并没有满足这个功能。 所以需要将Typed类定义成数据描述符 '''

Step2:在Step1里确定了要定义Typed为数据描述符,那Step2就来定义数据描述符

class Typed: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print("get方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) print("owner参数是[%s]" %owner) # owner:是实例的拥有者 def __set__(self, instance, value): print("set方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) print("value参数是[%s]" %value) def __delete__(self, instance): print("delete方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) class People: name = Typed() # 限制name被一个数据描述符代理 def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary p1 = People('alex', 24, 25000) # set方法被调用 # instance参数是[<__main__.People object at 0x01862F30>] # value参数是[alex] ''' 现在: (1)name类属性被一个数据描述符Typed代理,对name属性进行赋值操作的时候就会触发描述符的set方法; (2)set方法就会接受2个参数,instance 和 value, (3)instance参数就是实例p1本身,value就是具体的赋给name的值 ''' # print(p1) # <__main__.People object at 0x01862F30> # 调用name属性, 就调用了描述符的get方法 print(p1.name) # get方法被调用 # instance参数是[<__main__.People object at 0x01072EF0>] # owner参数是[<class '__main__.People'>] # 给name属性重新赋值, 调用set方法,跟实例化时一样了 p1.name = 'chou egg' # set方法被调用 # instance参数是[<__main__.People object at 0x00B52F30>] # value参数是[chou egg] # 实例的name属性值被存在哪里了呢? print(p1.__dict__) # {'age': 24, 'salary': 25000} ''' 为什么没有name属性呢? 因为name属性被数据描述符代理了,数据描述符比实例有更高的优先级, 所以实例化,或者修改值时, self.name = name触发的就是数据描述符了,而不再是实例, 所以实例的字典属性里没有name属性 ''' print(Typed.__dict__) # {'__module__': '__main__', '__get__': <function Typed.__get__ at 0x01650BB8>, # '__set__': <function Typed.__set__ at 0x01650B70>, # '__delete__': <function Typed.__delete__ at 0x01650B28>, # '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'Typed' objects>, # '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'Typed' objects>, '__doc__': None} ''' 数据描述符的属性字典里也没有name?那name被存在哪里了呢?

其实,上面的set方法,虽然接受了参数,却没有真正的进行设置和存储,所以在属性字典里是没有的 '''

Step3:设置和存储值

class Typed: def __get__(self, instance, owner): print("get方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) print("owner参数是[%s]" %owner) # owner:是实例的拥有者 def __set__(self, instance, value): print("set方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) print("value参数是[%s]" %value) print(self) # 看看self是谁 # <__main__.Typed object at 0x01749350>,是Typed产生的对象 # 要存的是实例的属性,所以要用instance #instance.__dict__['name'] = value # 这样写就把程序写死了,只能接收一个name,其他的都接受不了 def __delete__(self, instance): print("delete方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) class People: name = Typed() # 限制name被一个数据描述符代理 def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary p1 = People('alex', 24, 25000)

# 写活了 class Typed(): def __init__(self,key): self.key = key def __get__(self, instance, owner): print("get方法被调用") # print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # print("owner参数是[%s]" %owner) # owner:是实例的拥有者 # 3. set里把值存下了,get的时候就要能返回值,从属性字典里取出来给它 return instance.__dict__[self.key] def __set__(self, instance, value): print("set方法被调用") # print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # print("value参数是[%s]" %value) # print(self) # 看看self是谁 # <__main__.Typed object at 0x01749350>,是Typed产生的对象,而name确实People的,所以不能用它,应该把值写到People的实例里去 # 1. 如果要写活,就得有人传把,谁来传? # 因为name的实例化是在Typed里的,所以可以在Typed里写个构造函数,传递key # 2. 这个值被写到(存到)哪里去了? # 下面的语句就直接写到实例p1的属性字典里去了 instance.__dict__[self.key] = value def __delete__(self, instance): print("delete方法被调用") #print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # 3.set存下了值,那当然可以删掉它了。 instance.__dict__.pop(self.key) class People: # 2. 在name实例化的时候就可以把key传入,key是谁,就是name name = Typed('name') # age = Typed('age') # 怎么样算写活了,如果age也想用描述符,就可以把age传给key def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary 备注,为了演示方便,注释了几行print语句 # 实例化的时候,描述符的set方法被调用 p1 = People('alex', 24, 25000) # set方法被调用 # 验证一下name的值被写到了实例p1的属性字典里了 print(p1.__dict__) # {'name': 'alex', 'age': 24, 'salary': 25000} # 修改一个name的值 p1.name = 'busy gay' # set方法被调用 print(p1.__dict__) # {'name': 'busy gay', 'age': 24, 'salary': 25000} # 调用实例的name属性,get方法被调用,并返回了name的值 print(p1.name) # get方法被调用 # alex # 删除 del p1.name # delete方法被调用 print(p1.__dict__) # {'age': 24, 'salary': 25000} ''' 上面的实例化,查询,修改,删除,都是绕到Typed进行操作的 那,绕了半天,你想干什么呢? 回到需求,就是为了检测和限制输入类型的 '''

Step4:实现类型检测和限制功能

class Typed(): def __init__(self,key): self.key = key def __get__(self, instance, owner): print("get方法被调用") # print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # print("owner参数是[%s]" %owner) # owner:是实例的拥有者 # 3. set里把值存下了,get的时候就要能返回值,从属性字典里取出来给它 return instance.__dict__[self.key] def __set__(self, instance, value): print("set方法被调用") # print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # print("value参数是[%s]" %value) # print(self) # 看看self是谁 # <__main__.Typed object at 0x01749350>,是Typed产生的对象 # 实现限制功能,判断一下如果传入的值不是字符串类型,就终止运行 if not isinstance(value,str): print("你传入的值不是字符串类型,不能输入") return # return的目的是在这个位置就终止运行 # 如果要写活,就得有人传把,谁来传? # 因为name的实例化是在Typed里的,所以可以在Typed里写个构造函数,传递key instance.__dict__[self.key] = value def __delete__(self, instance): print("delete方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # 3.set存下了值,那当然可以删掉它了。 instance.__dict__.pop(self.key) class People: # 2. 在name实例化的时候就可以把key传入,key是谁,就是name name = Typed('name') # age = Typed('age') # 怎么样算写活了,如果age也想用描述符,就可以把age传给key def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary # 实例化的时候是name是字符串,正常执行 p1 = People('alex', 24, 25000) # 修改的时候,是个整型 p1.name = 15 # 你传入的值不是字符串类型,不能输入 ''' 上面已经实现了对name的限制和检测,那想实现其他的呢? '''

但是,上面的玩法还不够高端,我了个擦,想闹哪样,如果出现异常,能不能抛出异常呢?

class Typed(): def __init__(self,key): self.key = key def __get__(self, instance, owner): print("get方法被调用") # print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # print("owner参数是[%s]" %owner) # owner:是实例的拥有者 # 3. set里把值存下了,get的时候就要能返回值,从属性字典里取出来给它 return instance.__dict__[self.key] def __set__(self, instance, value): print("set方法被调用") # print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # print("value参数是[%s]" %value) # print(self) # 看看self是谁 # <__main__.Typed object at 0x01749350>,是Typed产生的对象 # 实现限制功能,判断一下如果传入的值不是字符串类型,就终止运行 if not isinstance(value,str): # print("你传入的值不是字符串类型,不能输入") # return # return的目的是在这个位置就终止运行 # 高端一点,擦,没看出来哪里高端,如果类型检查不是字符串,直接抛出异常,程序崩溃了 raise TypeError("你传入的不是字符串") # 如果要写活,就得有人传把,谁来传? # 因为name的实例化是在Typed里的,所以可以在Typed里写个构造函数,传递key instance.__dict__[self.key] = value def __delete__(self, instance): print("delete方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # 3.set存下了值,那当然可以删掉它了。 instance.__dict__.pop(self.key) class People: # 2. 在name实例化的时候就可以把key传入,key是谁,就是name name = Typed('name') # age = Typed('age') # 怎么样算写活了,如果age也想用描述符,就可以把age传给key def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary # 实例化的时候是name是字符串,正常执行 p1 = People('alex', 24, 25000) # 修改的时候,是个整型 p1.name = 15 # 传入的name不是字符串 p2 = People(213,23,25000) print(p2.__dict__)

Step5:上面已经实现了针对name的类型检查,那除了name以为,还有age和salary,是否也可以做类型检查那?

class Typed(): def __init__(self,key): self.key = key def __get__(self, instance, owner): print("get方法被调用") return instance.__dict__[self.key] def __set__(self, instance, value): print("set方法被调用") # 实现限制功能,判断一下如果传入的值不是字符串类型,就终止运行 if not isinstance(value,str): # 高端一点,擦,没看出来哪里高端,如果类型检查不是字符串,直接抛出异常,程序崩溃了 raise TypeError("你传入的不是字符串") # 如果要写活,就得有人传把,谁来传? # 因为name的实例化是在Typed里的,所以可以在Typed里写个构造函数,传递key instance.__dict__[self.key] = value def __delete__(self, instance): print("delete方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) # 3.set存下了值,那当然可以删掉它了。 instance.__dict__.pop(self.key) class People: # 2. 在name实例化的时候就可以把key传入,key是谁,就是name name = Typed('name') age = Typed('age') # age = Typed('age') # 怎么样算写活了,如果age也想用描述符,就可以把age传给key def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary # 实例化的时候是name是字符串,正常执行 p1 = People('alex', '24', 25000) # set方法被调用 # set方法被调用 print(p1.__dict__) # {'name': 'alex', 'age': '24', 'salary': 25000} ''' set方法被执行了2次,age还是个字符串而且也成功了。 首先,set被调用两次,是因为,实例化的时候,name被代理了调用了一次,age也被代理了,也调用了一次 其次,age应该是传入整形的,但是字符串却也传入成功了,写入了实例的属性字典了,这是一个不合理的地方。但是它又没报错,为什么? 原因: set里做类型判断的时候 if not isinstance(value,str),只校验了字符串,所以字符串形式的age值'24'就能正确执行,而事实上,我们期望 的应该是age为'24'字符串形式是应该报错的。 这就是判断的时候写死了,只能校验字符串了。那怎么才能写活呢? ''' # 再验证一下,如果age写为整形24的时候,不应该报错,却报错了 p2 = People('alex',23, 23400) # TypeError: 你传入的不是字符串

Step6:从Step5里,验证得知,类型校验被写死了,下面解决写活的问题----大功告成

class Typed(): def __init__(self,key,expected_type): # 实例化的时候传入一个期望类型 self.key = key self.expected_type = expected_type def __get__(self, instance, owner): print("get方法被调用") return instance.__dict__[self.key] def __set__(self, instance, value): print("set方法被调用") # 判断,如果接收的值不是期望类型,就抛出异常 if not isinstance(value,self.expected_type): raise TypeError("%s你传入的不是期望类型%s"%(self.key, self.expected_type)) instance.__dict__[self.key] = value def __delete__(self, instance): print("delete方法被调用") print("instance参数是[%s]" %instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.key) class People: name = Typed('name',str) # name的期望类型,传给代理描述符,在实例化的时候通过expected_type接收 age = Typed('age',int) # age的期望类型,传给代理描述符,在实例化的时候通过expected_type接收 def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary # 测试name传入的类型为非字符串 p1 = People(213, '24', 25000) # TypeError: name你传入的不是期望类型<class 'str'> # 验证age的值的类型不是整形 p2 = People('alex','23', 23400) # TypeError: age你传入的不是期望类型<class 'int'> # 验证传入的值类型与期望类型一致 p3 = People('alex',23, 23400) print(p3.__dict__) # {'name': 'alex', 'age': 23, 'salary': 23400}

上面的程序已经实现了类型检测的功能,但是如果People有很多个参数,都有进行类型限制怎么办?都像下面那样一直加下去吗?

有什么办法可以解决这个问题呢?

【答】类的装饰器可以解决这个问题

class People: # 如果People还有新增的属性,也需要进行类型限制,你都这么加吗? # 而且你还不知道有多少属性要加? # 有什么办法可以解决吗? name = Typed('name',str) age = Typed('age',int) salary = Typed('salary',float) ....... def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name = name self.age =age self.salary = salary

补充:类的装饰器知识点

1. 回顾装饰器的基本原理

# 写个高阶函数 def deco(func): print("======") return func # 想给test函数加功能,直接就@deco给test函数就行了 @deco # 做的事就是,给deco传进被装饰的函数test, 即deco(test),然后得到一个返回值再赋值给 test = deco(test) def test(): print("test函数运行啦") test() # ====== # test函数运行啦

2. 同样的道理,这是基本原理,也可以修饰类了。

# 同理,也可以修饰类 def deco(obj): print("======",obj) return obj @deco # Foo = deco(Foo) class Foo: pass f1 = Foo() print(f1)

3. 可以在装饰器里对类进行操作

def deco(obj): print("======",obj) # 类既然被拿到了,就可以对类进行调用,赋值,修改,删除等操作了 obj.x = 1 obj.y = 2 obj.z = 3 # 调用完类之后,再返回类 return obj @deco # Foo = deco(Foo) class Foo: pass # 那上面的操作,最后存在哪里了呢 print(Foo.__dict__) # {'__module__': '__main__', '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'Foo' objects>, # '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'Foo' objects>, '__doc__': None, # 'x': 1, 'y': 2, 'z': 3}

上面演示了类的装饰器的基本原理。

类的装饰器增强版

需求:类Bar,需要增加一个其他属性,破解写死的缺陷

装饰器被写死了

装饰器被写死了

破解写死的缺陷,怎么破?

函数嵌套,外面套一层

# 外面套一层,负责接收参数 def Typed(**kwargs): def deco(obj): # print("======",kwargs) for key,val in kwargs.items(): setattr(obj, key, val) # 调用完类之后,再返回类 return obj # print("===",kwargs) return deco # @deco # Foo = deco(Foo) # class Foo: # pass # 给Bar加参数,但是deco里却写死了 # 1. Typed(x=1, y =2, x=3) --->deco,deco此时变成了局部作用域 # 2. @deco---> Foo = deco(Foo) @Typed(x=1, y =2, z=3) class Bar: pass @Typed(name = 'egon', age = 34) class Car: pass print(Car.__dict__) # {'__module__': '__main__', '__dict__': <attribute '__dict__' of 'Car' objects>, # '__weakref__': <attribute '__weakref__' of 'Car' objects>, # '__doc__': None, 'name': 'egon', 'age': 34} print(Car.name) # egon

Step7.破解了装饰器写死的问题,下面就看看如何用装饰器解决给类增加属性且实现类型限制的功能

class Typed: def __init__(self,key,expected_type): self.key=key self.expected_type=expected_type def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get方法') return instance.__dict__[self.key] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set方法') if not isinstance(value,self.expected_type): raise TypeError('%s 传入的类型不是%s' %(self.key,self.expected_type)) instance.__dict__[self.key]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete方法') instance.__dict__.pop(self.key) def deco(**kwargs): #kwargs={'name':str,'age':int} def wrapper(obj): #obj=People for key,val in kwargs.items():#(('name',str),('age',int)) setattr(obj,key,Typed(key,val)) # setattr(People,'name',Typed('name',str)) #People.name=Typed('name',str) return obj return wrapper # name=str,age=int代表name就要去str类型,age就要求是int类型 ''' @deco其实做了2件事: 1. 调用deco(),加了()就会运行,返回wrapper,就变成了@wrapper 2. @wrapper也加了(),就会运行wrapper()函数,返回obj,obj代表People ''' @deco(name=str,age=int) class People: name='alex' # name=Typed('name',str) # age=Typed('age',int) def __init__(self,name,age,salary,gender,heigth): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary

6 描述符总结

描述符是可以实现大部分python类特性中的底层魔法,包括@classmethod,@staticmethd,@property甚至是__slots__属性

描述符是很多高级库和框架的重要工具之一,描述符通常是使用到装饰器或者元类的大型框架中的一个组件.

7 利用描述符原理完成一个自定制@property,实现延迟计算(本质就是把一个函数属性利用装饰器原理做成一个描述符:类的属性字典中函数名为key,value为描述符类产生的对象)

class Room(): def __init__(self, name, width, length): self.name = name self.width = width self.length = length # 定义求面积的方法 # 做出一个静态方法,隐藏起来,让外面的用户不知道调用的内部过程 @property # area=property(area) 相当于给类加了一个property静态属性;@property此时相当于是Room的类属性 def area(self): return self.width * self.length r1 = Room('桃花源', 100, 200) print(r1.area) # 20000

上面的@property是调用的Python自己的,下面自己做一个property

Step1.先搭个架子,实现类似@property的方法

# 定义一个类似property的类lazyproperty class lazyproperty: def __init__(self,func): self.func = func class Room(): def __init__(self, name, width, length): self.name = name self.width = width self.length = length ''' @语法糖的两个知识点: 1. @lazyproperty后面没有直接加() # 相当于 lazyproperty加()进行运行,运行就会把@lazyproperty下面函数的名字area传给lazyproperty进行 # 运行lazyproperty就是在进行 class lazyproperty的实例化,就会触发class lazyproperty的__init__方法 # 运行的结果再赋值给 area=lazyproperty(area) 2. @lazyproperty后加了(),即@lazyproperty(),就意味着可以传参数 # 如:@lazyproperty(name = str, age = int) # 实际运行的时候,就是先运行@lazyproperty(name = str, age = int)得到一个结果如 res,变成 # @res, 然后再像1那样运行。 ''' @lazyproperty def area(self): return self.width * self.length r1 = Room('别野',200,20) print(r1.area) # <__main__.lazyproperty object at 0x00B32F10>

# 到这里,已经能定位到 lazyproperty 这个对象了,下面就差让他运行返回结果就可以了。

Step2. 实现利用描述符,触发area运行,返回运行结果

# 定义一个类似property的类lazyproperty class Lazyproperty: def __init__(self,func): self.func = func # 把Lazyproperty做成描述符 ''' 描述符__get__方法,有2个参数,一个是instance,一个是owner 描述是代理别的类的属性,这个类会衍生出2个对象,一个是类自己,一个是由类实例化后的实例,这两个对象都可以调用 代理的属性,只要调用就会触发描述符的__get__方法,但是两个人在调用的时候触发的传入的值不一样: 类调用的时候传入的instance是None, 实例调用的时候传入的instance是实例自己 ''' def __get__(self, instance, owner): if instance is None: return self val = self.func(instance) return val class Room(): area = Lazyproperty def __init__(self, name, width, length): self.name = name self.width = width self.length = length ''' @语法糖的两个知识点: 1. @lazyproperty后面没有直接加() # 相当于 lazyproperty加()进行运行,运行就会把@lazyproperty下面函数的名字area传给lazyproperty进行 # 运行lazyproperty就是在进行 class lazyproperty的实例化,就会触发class lazyproperty的__init__方法 # 运行的结果再赋值给 area=lazyproperty(area) 2. @lazyproperty后加了(),即@lazyproperty(),就意味着可以传参数 # 如:@lazyproperty(name = str, age = int) # 实际运行的时候,就是先运行@lazyproperty(name = str, age = int)得到一个结果如 res,变成 # @res, 然后再像1那样运行。 ''' @Lazyproperty def area(self): return self.width * self.length

Step3:实现一个数据存储功能,让下次调用可以直接从字典里取值

上面的方法计算一次,下次再计算的时候,还是会去调用get方法,能否实现计算一次,下次再去调用就不用再去计算了,而是直接从某个地方拿结果就行了Python自带的property实现不了,那自定义的Lazyproperty就可以自己实现这个功能

# 定义一个类似property的类lazyproperty class Lazyproperty: def __init__(self,func): self.func = func # 把Lazyproperty做成非数据描述符 def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get方法触发了') if instance is None: return self val = self.func(instance) # 再因为这个描述符被定义成了一个非数据描述符,而实例属性的优先级高于非数据描述符 # 又把计算的结果放到实例自己的属性字典里 # 所以下次再调的时候,实例的属性字典里已经有了,就会直接从实例的属性字典里取值,而不会再次 # 调描述符,不调描述符就不会触发func的运行,也就不会触发area的再次运行 setattr(instance, self.func.__name__, val) return val class Room(): area = Lazyproperty def __init__(self, name, width, length): self.name = name self.width = width self.length = length @Lazyproperty def area(self): return self.width * self.length @property def area1(self): return self.width * self.length r1 = Room('别野',200,20) print(r1.area) print(r1.__dict__) # {'name': '别野', 'width': 200, 'length': 20, 'area': 4000} print(r1.area) print(r1.area)

下面的是copy的原装货(thanks 老男孩linhaifeng的贡献)

class Str:

def __init__(self,name):

self.name=name

def __get__(self, instance, owner):

print('get--->',instance,owner)

return instance.__dict__[self.name]

def __set__(self, instance, value):

print('set--->',instance,value)

instance.__dict__[self.name]=value

def __delete__(self, instance):

print('delete--->',instance)

instance.__dict__.pop(self.name)

class People:

name=Str('name')

def __init__(self,name,age,salary):

self.name=name

self.age=age

self.salary=salary

p1=People('egon',18,3231.3)

#调用

print(p1.__dict__)

p1.name

#赋值

print(p1.__dict__)

p1.name='egonlin'

print(p1.__dict__)

#删除

print(p1.__dict__)

del p1.name

print(p1.__dict__)

class Str: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name') def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary #疑问:如果我用类名去操作属性呢 People.name #报错,错误的根源在于类去操作属性时,会把None传给instance #修订__get__方法 class Str: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name') def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary print(People.name) #完美,解决 拔刀相助

class Str: def __init__(self,name,expected_type): self.name=name self.expected_type=expected_type def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) if not isinstance(value,self.expected_type): #如果不是期望的类型,则抛出异常 raise TypeError('Expected %s' %str(self.expected_type)) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Str('name',str) #新增类型限制str def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People(123,18,3333.3)#传入的name因不是字符串类型而抛出异常

class Typed: def __init__(self,name,expected_type): self.name=name self.expected_type=expected_type def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) if not isinstance(value,self.expected_type): raise TypeError('Expected %s' %str(self.expected_type)) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) class People: name=Typed('name',str) age=Typed('name',int) salary=Typed('name',float) def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People(123,18,3333.3) p1=People('egon','18',3333.3) p1=People('egon',18,3333)

大刀阔斧之后我们已然能实现功能了,但是问题是,如果我们的类有很多属性,你仍然采用在定义一堆类属性的方式去实现,low,这时候需要来一招:独孤九剑

def decorate(cls): print('类的装饰器开始运行啦------>') return cls @decorate #无参:People=decorate(People) class People: def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People('egon',18,3333.3)

def typeassert(**kwargs): def decorate(cls): print('类的装饰器开始运行啦------>',kwargs) return cls return decorate @typeassert(name=str,age=int,salary=float) #有参:1.运行typeassert(...)返回结果是decorate,此时参数都传给kwargs 2.People=decorate(People) class People: def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary p1=People('egon',18,3333.3)

终极大招

class Typed: def __init__(self,name,expected_type): self.name=name self.expected_type=expected_type def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('get--->',instance,owner) if instance is None: return self return instance.__dict__[self.name] def __set__(self, instance, value): print('set--->',instance,value) if not isinstance(value,self.expected_type): raise TypeError('Expected %s' %str(self.expected_type)) instance.__dict__[self.name]=value def __delete__(self, instance): print('delete--->',instance) instance.__dict__.pop(self.name) def typeassert(**kwargs): def decorate(cls): print('类的装饰器开始运行啦------>',kwargs) for name,expected_type in kwargs.items(): setattr(cls,name,Typed(name,expected_type)) return cls return decorate @typeassert(name=str,age=int,salary=float) #有参:1.运行typeassert(...)返回结果是decorate,此时参数都传给kwargs 2.People=decorate(People) class People: def __init__(self,name,age,salary): self.name=name self.age=age self.salary=salary print(People.__dict__) p1=People('egon',18,3333.3)

自制@property

class Room: def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length @property def area(self): return self.width * self.length r1=Room('alex',1,1) print(r1.area)

class Lazyproperty: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('这是我们自己定制的静态属性,r1.area实际是要执行r1.area()') if instance is None: return self return self.func(instance) #此时你应该明白,到底是谁在为你做自动传递self的事情 class Room: def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length @Lazyproperty #area=Lazyproperty(area) 相当于定义了一个类属性,即描述符 def area(self): return self.width * self.length r1=Room('alex',1,1) print(r1.area)

class Lazyproperty: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('这是我们自己定制的静态属性,r1.area实际是要执行r1.area()') if instance is None: return self else: print('--->') value=self.func(instance) setattr(instance,self.func.__name__,value) #计算一次就缓存到实例的属性字典中 return value class Room: def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length @Lazyproperty #area=Lazyproperty(area) 相当于'定义了一个类属性,即描述符' def area(self): return self.width * self.length r1=Room('alex',1,1) print(r1.area) #先从自己的属性字典找,没有再去类的中找,然后出发了area的__get__方法 print(r1.area) #先从自己的属性字典找,找到了,是上次计算的结果,这样就不用每执行一次都去计算

#缓存不起来了 class Lazyproperty: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): print('这是我们自己定制的静态属性,r1.area实际是要执行r1.area()') if instance is None: return self else: value=self.func(instance) instance.__dict__[self.func.__name__]=value return value # return self.func(instance) #此时你应该明白,到底是谁在为你做自动传递self的事情 def __set__(self, instance, value): print('hahahahahah') class Room: def __init__(self,name,width,length): self.name=name self.width=width self.length=length @Lazyproperty #area=Lazyproperty(area) 相当于定义了一个类属性,即描述符 def area(self): return self.width * self.length print(Room.__dict__) r1=Room('alex',1,1) print(r1.area) print(r1.area) print(r1.area) print(r1.area) #缓存功能失效,每次都去找描述符了,为何,因为描述符实现了set方法,它由非数据描#述符变成了数据描述符,数据描述符比实例属性有更高的优先级,因而所有的属性操# 作都去找描述符了

8 利用描述符原理完成一个自定制@classmethod

class ClassMethod: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): #类来调用,instance为None,owner为类本身,实例来调用,instance为实例,owner为类本身, def feedback(): print('在这里可以加功能啊...') return self.func(owner) return feedback class People: name='linhaifeng' @ClassMethod # say_hi=ClassMethod(say_hi) def say_hi(cls): print('你好啊,帅哥 %s' %cls.name) People.say_hi() p1=People() p1.say_hi() #疑问,类方法如果有参数呢,好说,好说 class ClassMethod: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): #类来调用,instance为None,owner为类本身,实例来调用,instance为实例,owner为类本身, def feedback(*args,**kwargs): print('在这里可以加功能啊...') return self.func(owner,*args,**kwargs) return feedback class People: name='linhaifeng' @ClassMethod # say_hi=ClassMethod(say_hi) def say_hi(cls,msg): print('你好啊,帅哥 %s %s' %(cls.name,msg)) People.say_hi('你是那偷心的贼') p1=People() p1.say_hi('你是那偷心的贼')

9 利用描述符原理完成一个自定制的@staticmethod

class StaticMethod: def __init__(self,func): self.func=func def __get__(self, instance, owner): #类来调用,instance为None,owner为类本身,实例来调用,instance为实例,owner为类本身, def feedback(*args,**kwargs): print('在这里可以加功能啊...') return self.func(*args,**kwargs) return feedback class People: @StaticMethod# say_hi=StaticMethod(say_hi) def say_hi(x,y,z): print('------>',x,y,z) People.say_hi(1,2,3) p1=People() p1.say_hi(4,5,6)

- 12.再看property

一个静态属性property本质就是实现了get,set,delete三种方法

class Foo: @property def AAA(self): print('get的时候运行我啊') @AAA.setter def AAA(self,value): print('set的时候运行我啊') @AAA.deleter def AAA(self): print('delete的时候运行我啊') #只有在属性AAA定义property后才能定义AAA.setter,AAA.deleter f1=Foo() f1.AAA f1.AAA='aaa' del f1.AAA

class Foo: def get_AAA(self): print('get的时候运行我啊') def set_AAA(self,value): print('set的时候运行我啊') def delete_AAA(self): print('delete的时候运行我啊') AAA=property(get_AAA,set_AAA,delete_AAA) #内置property三个参数与get,set,delete一一对应 f1=Foo() f1.AAA f1.AAA='aaa' del f1.AAA

怎么用?

class Goods: def __init__(self): # 原价 self.original_price = 100 # 折扣 self.discount = 0.8 @property def price(self): # 实际价格 = 原价 * 折扣 new_price = self.original_price * self.discount return new_price @price.setter def price(self, value): self.original_price = value @price.deleter def price(self): del self.original_price obj = Goods() obj.price # 获取商品价格 obj.price = 200 # 修改商品原价 print(obj.price) del obj.price # 删除商品原价

#实现类型检测功能 #第一关: class People: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name @property def name(self): return self.name # p1=People('alex') #property自动实现了set和get方法属于数据描述符,比实例属性优先级高,所以你这面写会触发property内置的set,抛出异常 #第二关:修订版 class People: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name #实例化就触发property @property def name(self): # return self.name #无限递归 print('get------>') return self.DouNiWan @name.setter def name(self,value): print('set------>') self.DouNiWan=value @name.deleter def name(self): print('delete------>') del self.DouNiWan p1=People('alex') #self.name实际是存放到self.DouNiWan里 print(p1.name) print(p1.name) print(p1.name) print(p1.__dict__) p1.name='egon' print(p1.__dict__) del p1.name print(p1.__dict__) #第三关:加上类型检查 class People: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name #实例化就触发property @property def name(self): # return self.name #无限递归 print('get------>') return self.DouNiWan @name.setter def name(self,value): print('set------>') if not isinstance(value,str): raise TypeError('必须是字符串类型') self.DouNiWan=value @name.deleter def name(self): print('delete------>') del self.DouNiWan p1=People('alex') #self.name实际是存放到self.DouNiWan里 p1.name=1

- 13. __enter__和__exit__

我们知道在操作文件对象的时候可以这么写

with open('a.txt') as f: '代码块'

上述叫做上下文管理协议,即with语句,为了让一个对象兼容with语句,必须在这个对象的类中声明__enter__和__exit__方法

class Open: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): print('出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量') # return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊') with Open('a.txt') as f: print('=====>执行代码块') # print(f,f.name)

class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('执行exit')# with Foo('a.txt')实例化触发 __enter__,__enter__返回的结果是self,self赋值给f # 然后执行with代码块里的逻辑 # 执行完毕后,会触发__exit__的运行 with Foo('a.txt') as f: print(f) print(f.name) print('-----------------') print('-----------------')

__exit__()中的三个参数分别代表异常类型,异常值和追溯信息,with语句中代码块出现异常,则with后的代码都无法执行

# with代码块没异常的时候,就正常执行,exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb返回值都是None class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('执行exit') print(exc_type) print(exc_val) print(exc_tb) return True with Foo('a.txt') as f: print(f) print(f.name) print("with 语句执行完了") # 结果 a.txt 执行exit None None None with 语句执行完了

class Open: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): print('出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量') def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊') print(exc_type) print(exc_val) print(exc_tb) with Open('a.txt') as f: print('=====>执行代码块') raise AttributeError('***着火啦,救火啊***') print('0'*100) #------------------------------->不会执行

# with代码块有异常,__exit__有返回True时

class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('执行exit') print(exc_type) print(exc_val) print(exc_tb) return True # 代表把上面的异常就吞了,意味着程序在此时没有异常出现 # with Foo('a.txt')实例化触发 __enter__,__enter__返回的结果是self,self赋值给f # 然后执行with代码块里的逻辑 # 执行完毕后,会触发__exit__的运行 with Foo('a.txt') as f: print(f) print(f.name) print('-----------------') print(rwefdreqr) ''' 异常时,触发__exit__, __exit__如果return True的话,表示这些异常被吞掉了,异常被吃掉了,意味着 print(rwefdreqr)后面代码块里的程序都不会在执行了 ''' print("会执行吗?") # 结果 <__main__.Foo object at 0x00D12ED0> a.txt ----------------- 执行exit <class 'NameError'> name 'rwefdreqr' is not defined <traceback object at 0x00D1B8F0>

# with代码块有异常,__exit__无返回True时

class Foo: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): return self def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('执行exit') print(exc_type) print(exc_val) print(exc_tb) # return True # 如果没有返回True,表示这个异常没有被吞掉,程序异常就终止了异常语句后面的运行,程序结束退出 with Foo('a.txt') as f: print(f) print(f.name) print('-----------------') print(rwefdreqr) ''' 异常时,触发__exit__, __exit__如果没有return True的话,表示这些异常没有被吞掉了,程序退出 with语句代码块外面的程序也不会被执行 ''' print("会执行吗?") print("with 语句执行完了")

如果__exit()返回值为True,那么异常会被清空,就好像啥都没发生一样,with后的语句正常执行

class Open: def __init__(self,name): self.name=name def __enter__(self): print('出现with语句,对象的__enter__被触发,有返回值则赋值给as声明的变量') def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): print('with中代码块执行完毕时执行我啊') print(exc_type) print(exc_val) print(exc_tb) return True with Open('a.txt') as f: print('=====>执行代码块') raise AttributeError('***着火啦,救火啊***') print('0'*100) #------------------------------->会执行

class Open: def __init__(self,filepath,mode='r',encoding='utf-8'): self.filepath=filepath self.mode=mode self.encoding=encoding def __enter__(self): # print('enter') self.f=open(self.filepath,mode=self.mode,encoding=self.encoding) return self.f def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_val, exc_tb): # print('exit') self.f.close() return True def __getattr__(self, item): return getattr(self.f,item) with Open('a.txt','w') as f: print(f) f.write('aaaaaa') f.wasdf #抛出异常,交给__exit__处理

用途或者说好处:

1.使用with语句的目的就是把代码块放入with中执行,with结束后,自动完成清理工作,无须手动干预

2.在需要管理一些资源比如文件,网络连接和锁的编程环境中,可以在__exit__中定制自动释放资源的机制,你无须再去关系这个问题,这将大有用处

__enter__和__exit__ 小总结:

1. with open('a.txt') 触发open('a.txt').__enter__(),拿到返回值

2. as f:表示将拿到的返回值赋值给f

3. with open('a.txt') as f 等同于 f = open('a.txt').__enter__()

4. 执行with代码块:

(1)没有异常的情况下,整个代码块运行完毕后去触发__exit__,它的三个参数都返回None

(2)有异常的情况下,从异常出现的位置直接触发__exit__:

a.如果__exit__的返回值是Ture,代表吞掉了异常,__exit__运行完毕就代表了整个with语句的执行完毕,然后接着执行with代码块之外的程序

b.如果__exit__的返回值不是Ture,代表吐出了异常,意味着整个程序在当前位置就有一个异常, 后面的代码都统统不执行了。

c.__exit__运行完毕就代表了整个with语句的执行完毕

5.with代码块执行完毕后,就会自动触发__exit__的执行。