原文链接:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5977675/

翻译人:FJTCM区块链开发学习小组 时间:2019/04/24

Secure and Trustable Electronic Medical Records Sharing using Blockchain

使用区块链进行安全可信的电子医疗记录共享

Abstract

Electronic medical records (EMRs) are critical, highly sensitive private information in healthcare, and need to be frequently shared among peers. Blockchain provides a shared, immutable and transparent history of all the transactions to build applications with trust, accountability and transparency. This provides a unique opportunity to develop a secure and trustable EMR data management and sharing system using blockchain. In this paper, we present our perspectives on blockchain based healthcare data management, in particular, for EMR data sharing between healthcare providers and for research studies. We propose a framework on managing and sharing EMR data for cancer patient care. In collaboration with Stony Brook University Hospital, we implemented our framework in a prototype that ensures privacy, security, availability, and fine-grained access control over EMR data. The proposed work can significantly reduce the turnaround time for EMR sharing, improve decision making for medical care, and reduce the overall cost.

摘要

电子病历(EMR)是医疗保健中的关键,高度敏感的私人信息,需要经常在同伴之间共享。 区块链提供了所有事务的共享,不可篡改和透明的历史记录,以构建具有信任,责任和透明度的应用程序。这为使用区块链开发安全可信的EMR数据管理和共享系统提供了独特的优势。在本文中,我们介绍了基于区块链的医疗数据管理的观点,特别是医疗服务提供者之间的EMR数据共享和研究。我们提出了一个管理和共享癌症患者护理的EMR数据的框架。我们与Stony Brook大学医院合作,在原型中实施了我们的框架,以确保隐私,安全性,可用性以及对EMR数据的细粒度访问控制。拟议的工作可以显着缩短EMR共享的周转时间,改善医疗保健决策,降低总体成本。

Introduction

Electronic medical records (EMRs) are critical but highly sensitive private information for diagnosis and treatment in healthcare, which need to be frequently distributed and shared among peers such as healthcare providers, insurance companies, pharmacies, researchers, patients families, among others. This poses a major challenge on keeping a patient’s medical history up-to-date. Storing and sharing data between multiple entities, maintaining access control through numerous consents only complicate the process of a patient’s treatment. A patient, suffering from a serious medical condition such as cancer, or HIV, has to maintain the long history of the treatment process and post-treatment rehabilitation and monitoring. Having access to a complete history may be crucial for his treatment: for instance, knowing the delivered radiation doses or laboratory results is necessary for continuing the treatment.

介绍

电子医疗记录(EMR)是医疗保健中诊断和治疗的关键且高度敏感的私人信息,需要经常在医疗服务提供者,保险公司,药房,研究人员,患者家属等同行之间进行分发和共享。 这对于保持患者的病史保持最新是一项重大挑战。 在多个实体之间存储和共享数据,通过许多同意维护访问控制只会使患者的治疗过程复杂化。 患有癌症或HIV等严重疾病的患者必须保持治疗过程和治疗后康复和监测的悠久历史。 获得完整的病史可能对他的治疗至关重要:例如,了解所提供的放射剂量或实验室结果是继续治疗所必需的。

A patient may visit multiple medical institutions for a consultation, or may be transferred from one hospital to another. According to the legislation1–4, a patient is given a right over his health information and may set rules and limits on who can look at and receive his health information. If a patient needs to share his clinical data for the research purposes, or transfer them from one hospital to another, he may be required to sign a consent that specifies what type of data will be shared, the information about the recipient, and the period during which the data can be accessed by the recipient. This may be extremely difficult to coordinate, especially when a patient is moving to another city, region, or country and may not know in advance the caregiver or hospital where he will be receiving care later on.

患者可以访问多个医疗机构进行咨询,也可以从一家医院转到另一家医院。 根据立法1-4,患者可以获得对其健康信息的权利,并可以对谁可以查看和接收他的健康信息设定规则和限制。 如果患者需要为研究目的分享他的临床数据,或者将他们从一家医院转移到另一家医院,他可能需要签署一份同意书,该同意书指定将分享哪种类型的数据,有关接收者的信息以及期间 在此期间,收件人可以访问数据。 这可能非常难以协调,特别是当患者移动到另一个城市,地区或国家并且可能事先不知道他将在何时接受护理的护理人员或医院。

Even if the consent is provided, the process of transferring the data is time consuming, especially if sending them by post. Sending the patients’ data via email over the Internet is not considered in most hospitals as this could impose security risk while the patient’s healthcare records are in transit1. Ecosystems for health information exchange (HIE) such as CommonWell Health Alliance aim to ensure that the data form patient electronic health record are securely, efficiently and accurately shared nationwide in US. This implies that once providers receives an access to the patient’s health information it is difficult to guarantee that a patient could receive independent opinions from different healthcare providers. Moreover, such ecosystems do not address the requirements in case of transferring data from one country to another.

即使提供了同意,传输数据的过程也很耗时,尤其是在通过邮寄方式发送时。 在大多数医院都没有考虑通过互联网通过电子邮件发送患者的数据,因为这可能会在患者的医疗记录在途时带来安全风险1。 CommonWell健康联盟等健康信息交换生态系统(HIE)旨在确保在美国全国范围内安全,有效和准确地共享患者电子健康记录中的数据。 这意味着一旦提供者接收到患者的健康信息,就很难保证患者可以从不同的医疗服务提供者那里获得独立意见。 此外,这种生态系统无法满足将数据从一个国家转移到另一个国家的要求。

Data aggregation for research purposes also requires the consent unless the data are anonymized. However, it has been shown that independent release of locally anonymized medical data corresponding to the same patient and originated from different sources (e.g., several healthcare institutions visited by the patient) could cause de-identification of the patient, and, therefore, violation of privacy

除非数据是匿名的,否则用于研究目的的数据聚合也需要得到同意。 然而,已经表明,对应于同一患者并且源自不同来源(例如,患者访问的几个医疗机构)的本地匿名医疗数据的独立发布可能导致患者的去识别,并且因此违反 隐私。

Relying on centralized entity that would store and manage the patients’ data and access control policies means having single point of failure and a bottleneck of the whole framework. It also requires either conducting all the operations (such as search, or anonymization) over encrypted data, or choosing a fully trusted entity that will have access to sensitive information about the patients. The former still requires management of large amounts of memory33 and is not suitable for hospital environment. The latter was proven to be very difficult to put in practice. An example of GoogleHealth wallet5 has shown that patients are concerned about their privacy and aware of the potential risk that their sensitive data might be misused.

依靠存储和管理患者数据和访问控制策略的集中实体意味着具有单点故障和整个框架的瓶颈。 它还要求对加密数据进行所有操作(例如搜索或匿名化),或者选择可以访问有关患者的敏感信息的完全可信实体。 前者仍需要管理大量内存33,不适合医院环境。 事实证明,后者很难付诸实践。 GoogleHealth wallet5的一个例子表明,患者关注他们的隐私,并意识到他们的敏感数据可能被滥用的潜在风险。

Having access to a ledger - shared, immutable, and transparent history of all the actions that have happened to all the participants of the network (such as a patient modifying permissions, a doctor, accessing or uploading new data, or sharing them for research) overcome the issues presented above. By providing the tool to achieve consensus among distributed entities without relying on a single trusted party, blockchain technology will guarantee data security, control over sensitive data, and will facilitate healthcare data management for the patient and different actors in medical domain. In the healthcare settings we can define a transaction as a process of creating, uploading or transferring EMR data that is performed within the connected peers. A set of transactions grouped at certain time is added to the ledger that records all the transaction and therefore represents the state of the network. The key benefits of applying the blockchain technology in healthcare are the following: verifiable and immutable transactions; tamper resistance, transparency, and integrity of distributed sensitive medical data. This is mainly achieved by employing consensus protocol and cryptographic primitives such as hashing and digital signatures.

可以访问分类帐 - 所有网络参与者发生的所有操作的共享,不可变和透明历史记录(例如患者修改权限,医生,访问或上传新数据或共享研究)克服上述问题。通过提供工具以在不依赖单个可信方的情况下在分布式实体之间达成共识,区块链技术将保证数据安全性,对敏感数据的控制,并将促进患者和医学领域中的不同参与者的医疗数据管理。在医疗保健设置中,我们可以将交易定义为创建,上传或传输在连接的对等体内执行的EMR数据的过程。在特定时间分组的一组事务被添加到记录所有事务的分类帐中,因此表示网络的状态。在医疗保健中应用区块链技术的主要好处如下:可验证和不可变的交易;防篡改,透明度和分布式敏感医疗数据的完整性。这主要通过采用共识协议和加密原语(例如散列和数字签名)来实现。

The possibility of using blockchain for healthcare data management has recently raised a lot of attention in both industry and academia7, 21, 27, 29. However, only one functioning prototype of a system that uses blockchain for medical data management has been proposed7. In our work, we focus on a practical implementation of a system that uses blockchain technology and can be integrated in clinical practice. We employ permissioned blockchain technology to maintain metadata and access control policy and a cloud service to store encrypted patients’ data. Combining these technologies allows us to guarantee data security and privacy as well as availability with respect to the access control policy defined by the patient.

使用区块链进行医疗保健数据管理的可能性最近在工业界和学术界引起了很多关注7,21,27,29。然而,只提出了一个使用区块链进行医疗数据管理的系统原型7。 在我们的工作中,我们专注于使用区块链技术的系统的实际实施,并且可以集成到临床实践中。 我们使用经过许可的区块链技术来维护元数据和访问控制策略以及用于存储加密患者数据的云服务。 结合这些技术,我们可以保证数据安全性和隐私以及患者定义的访问控制策略的可用性。

The contribution of the paper is twofold. First, we propose multiple scenarios of blockchain applications in healthcare and analyze existing technology implementations that could be used to put the scenarios in practice. Second, we present a framework for blockchain based data sharing for primary care of oncology patients under cancer treatment. We developed a prototype in collaboration with the Department of Radiation Oncology in a major US hospital. Therefore, the functionality of the prototype is expected to meet the requirements from medical practice perspective.

论文的贡献是双重的。 首先,我们提出了医疗保健中区块链应用的多种情景,并分析了可用于将情景付诸实践的现有技术实施。 其次,我们提出了基于区块链的数据共享框架,用于癌症治疗的肿瘤患者的初级保健。 我们与美国一家大型医院的放射肿瘤科合作开发了一个原型。 因此,原型的功能有望满足医疗实践的要求。

1. Background on Blockchain

Blockchain is a peer-to-peer distributed ledger technology that was initially used in the financial industry.11. Based on how the identity of a user is defined within a network, one could distinguish between permissioned and permissionless blockchain systems. A permissionless system is one in which the identities of participants are either pseudonymous or even anonymous20 and every user may append a new block to the ledger. In contrast, in case of a permissioned blockchain, the identity of a user is controlled by an identity provider. The identity provider is trusted to maintain access control within the network and the user’s rights to participate in the consensus, or validate a new block. Next we introduce two most well-known implementations of the blockchain technology: Ethereum8 and Hyperledger11.

1.区块链背景

区块链是一种点对点分布式分类账技术,最初用于金融业。 基于如何在网络中定义用户的身份,可以区分许可和无权限的区块链系统。 无权限系统是指参与者的身份是假名或甚至是匿名的系统,并且每个用户可以将新的块附加到分类帐。 相反,在许可的区块链的情况下,用户的身份由身份提供者控制。 身份提供者被信任以维护网络内的访问控制以及用户参与共识或验证新块的权利。 接下来,我们介绍两种最着名的区块链技术实现:Ethereum8和Hyperledger11。

1.1. Permissionless Blockchain Implementation

Ethereum8 is an implementation of a permissionless programmable blockchain that allows any user to create and execute the code of arbitrary algorithmic complexity on the Ethereum platform: Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). “Accounts” of two types could be created on EVM. Externally owned account (EOA) is an account controlled by a private key of a user. Contract account is the second type of accounts that can be seen as an autonomous agent that lives in the Ethereum execution environment and is controlled by its contract code: smart contract. Smart contract is used to encode arbitrary state transition functions, allowing users to create systems with different functionalities by transforming the logic of the system into the code.

1.1。 无权的区块链实施

Ethereum8是一种无权可编程区块链的实现,允许任何用户在以太坊平台上创建和执行任意算法复杂度的代码:以太坊虚拟机(EVM)。 可以在EVM上创建两种类型的“帐户”。 外部拥有帐户(EOA)是由用户的私钥控制的帐户。 合同帐户是第二种类型的帐户,可以看作是一个自治代理,它位于以太坊执行环境中,并由合同代码控制:智能合约。 智能契约用于编码任意状态转换函数,允许用户通过将系统逻辑转换为代码来创建具有不同功能的系统。

Code execution in Ethereum must be paid. The transaction price limits the number of computational steps for the code execution in order to prevent infinite loops or other computational wastage. Users could participate in a consensus process to obtain the tokens to be paid for transaction execution. In Ethereum, the consensus is achieved by using a proof-of-work (PoW) mechanism. PoW is based on “mining”: finding a nonce input to the algorithm so that the resulting hash of a new valid block satisfies certain requirements. These requirements set the difficulty threshold for the process of finding the nonce12

必须支付以太坊中的代码执行权。 交易价格限制了代码执行的计算步骤的数量,以防止无限循环或其他计算浪费。 用户可以参与共识过程以获得为交易执行而支付的代币。 在以太坊中,通过使用工作量证明(PoW)机制实现了共识。 PoW基于“挖掘”:找到算法的随机数输入,以便新的有效块的结果散列满足某些要求。 这些要求为寻找nonce12的过程设定了难度阈值。

The difficulty threshold impacts the amount of energy to be spent to find such nonce. For example, the amount of energy used by Bitcoin mining is comparable to the Irish national energy consumption15. Existing PoW blockchains can achieve throughput of not more than 60 transactions per second without significantly affecting the blockchain’s security13. These two findings show that PoW can negatively impact the system scalability and overall throughput14.

难度阈值影响用于找到这种随机数的能量。 例如,比特币采矿所使用的能源数量与爱尔兰国家能源消耗相当15。 现有的PoW区块链可以实现每秒不超过60个事务的吞吐量,而不会显着影响区块链的安全性13。 这两项研究结果表明,PoW会对系统可扩展性和整体吞吐量产生负面影响14。

Proof-of-Stake (PoS)16 and Proof-of-Burn (PoB)17, or virtual mining mechanisms, have been recently proposed as alternatives to PoW. Instead of having participants mine by exchanging their wealth for computational resources (which are then exchanged for mining rewards), in virtual mining, participants could exchange their wealth directly for the ability to append a new block to the ledger18. For example, in PoS, selection of a participant that will create a new block is based on the amount of tokens owned by the participant, in PoB – based on the amount of tokens “burnt” (sent to an unspendable address). However, providing a rigorous argument for or against the stability of virtual mining remains an open problem18.

最近提出了证明(PoS)16和烧伤证明(PoB)17或虚拟挖掘机制作为PoW的替代方案。 在虚拟挖掘中,参与者可以直接交换财富,以便能够将新的块附加到分类账,而不是让参与者通过交换他们的财富来获取计算资源(然后交换为采矿奖励)。 例如,在PoS中,选择将创建新块的参与者是基于参与者拥有的令牌数量,以PoB为基础 - 基于令牌“烧毁”(发送到不可靠地址)的数量。 然而,提供支持或反对虚拟采矿稳定性的严格论据仍然是一个悬而未决的问题。

1.2. Permissioned Blockchain Implementation

In the case of a permissionned system, users do not have an incentive to cheat as their identity is revealed to the identity server. Moreover, participation in consensus management is restricted to a predefined set of users. This opens a possibility to use a state machine replication algorithm (such as PBFT19) as a consensus mechanism. Hyperledger11 – an implementation of a permissioned blockchaian – is an open source blockchain initiative hosted by the Linux Foundation. Hyperledger has a modular architecture that allows plugging in different consensus mechanisms, including PBFT. Hyperledger services could be logically grouped in three categories: Membership services, Blockchain services, and Chaincode services10.

1.2。 许可的区块链实施

在许可系统的情况下,用户没有欺骗的动机,因为他们的身份被透露给身份服务器。 此外,参与共识管理仅限于一组预定义的用户。 这开启了使用状态机复制算法(例如PBFT19)作为共识机制的可能性。 Hyperledger11 - 一个允许的区块链的实现 - 是由Linux基金会托管的开源区块链计划。 Hyperledger具有模块化架构,允许插入不同的共识机制,包括PBFT。 Hyperledger服务可以在逻辑上分为三类:成员服务,区块链服务和Chaincode服务10。

Membership services manage identity, privacy, and confidentiality on the network. A user is assigned a username and a password that will be used to issue the Enrollment certificate (ECert) to identify every registered user. It is possible to use different Transaction certificates (TCert) associated with the same ECert for every transaction to ensure their unlinkability (a mapping between TCert and Ecert are only known to the membership service). Blockchain services manage the distributed ledger through a peer-to-peer protocol built on HTTP/2. In Hyperledger, smart contracts are implemented by the chaincode. Chaincode services provide a secure way to execute smart contracts on validating nodes.

会员服务管理网络上的身份,隐私和机密性。 为用户分配用户名和密码,用于颁发注册证书(ECert)以标识每个注册用户。 对于每个事务,可以使用与相同ECert相关联的不同事务证书(TCert)来确保它们的不可链接性(TCert和Ecert之间的映射仅为成员服务所知)。 区块链服务通过基于HTTP / 2构建的对等协议来管理分布式分类帐。 在Hyperledger中,智能合约由链码实现。 Chaincode服务提供了一种在验证节点上执行智能合约的安全方法。

In Hyperledger, smart contracts are implemented by chaincode that consist of Logic and associated World State (State). Logic of the chaincode is a set of rules that define how transactions will be executed and how State will change. State is a database that stores the information in a form of keys and values that are arbitrary byte arrays. The State also contains the block number to which it corresponds. Ledger manages blockchain by including an efficiently cryptographic hash of the State when appending a block. This allows efficient synchronization if a node was temporary off-line, minimizing the amount of stored data at the node11

在Hyperledger中,智能合约由链码实现,链码由逻辑和相关的世界状态(State)组成。 链码的逻辑是一组规则,用于定义如何执行事务以及状态如何更改。 State是一个数据库,它以键和值的形式存储信息,这些值是任意字节数组。 状态还包含与其对应的块编号。 Ledger通过在附加块时包含State的有效加密哈希来管理区块链。 如果节点是临时离线的,则允许有效同步,从而最小化节点11处存储的数据量

2. Potential Blockchain Applications in Healthcare

Blockchain provides a unique opportunity to support healthcare. In this section, we propose three scenarios: primary patient care, medical research, and connected health. Figure 1 shows a graphical representation of the combination of the aforementioned scenarios.

Scenarios of using blockchain in different healthcare settings: Scenario 1: Primary patient care; Scenario 2: Data aggregation for the research purposes; Scenario 3: Connecting different healthcare players for better patient care.

Scenario 1: Primary Patient Care. Using blockchain technology for primary patient care can help to address the following problems of the current healthcare systems:

- A patient often visits multiple disconnected hospitals. He has to keep the history of all his data and maintain the updates. This leads to the situation when required information may not be available.

- Due to the unavailability of the data, patient may have to repeat some tests for laboratory results. This is common when the results are stored in another hospital and can not be immediately accessed.

- The healthcare data are sensitive and their management is cumbersome. Yet, there is no privacy-preserving system in clinical practice that allows patients to maintain access control policy in an efficient manner.

- Sharing data between different healthcare providers may require major effort and could be time consuming.

Next, we propose two approaches that can be implemented separately or combined to improve patient care.

- Institution-based: The network would be formed by the trusted peers: healthcare institutions or general practitioners (caregivers). The peers will run consensus protocol and maintain a distributed ledger. The patient (or his relatives) will be able to access and manage his data through an application at any node where his information is stored. If a peer is off-line, a patient could access the data through any other online node. The key management process and the access control policy will be encoded in a chaincode, thus, ensuring data security and patient’s privacy.

- Case specific (serious medical conditions, examination, elderly care): During a patient’s stay in a hospital for treatment, rehabilitation, examination, or surgery, a case-specific ledger could be created. The network would connect doctors, nurses, and family to achieve efficiency and transparency of the treatment. This will help to eliminate human-made mistakes, to ensure consensus in case of a debate about certain stage of the treatment.

2.潜在的区块链在医疗保健中的应用

区块链提供了支持医疗保健的独特机会。 在本节中,我们提出了三种情景:初级患者护理,医学研究和相关健康。 图1显示了上述场景组合的图形表示。。

在不同医疗环境中使用区块链的情景:

情景1:初级患者护理。 使用区块链技术进行初级患者护理可以帮助解决当前医疗保健系统的以下问题:

患者经常访问多个断开连接的医院。他必须保留所有数据的历史记录并保持更新。这导致可能无法获得所需信息的情况。

由于数据不可用,患者可能不得不重复一些实验室结果测试。当结果存储在另一家医院并且无法立即访问时,这种情况很常见。

医疗数据是敏感的,他们的管理很麻烦。然而,临床实践中没有隐私保护系统允许患者以有效的方式维护访问控制策略。

在不同医疗服务提供者之间共享数据可能需要大量工作并且可能是耗时的

接下来,我们提出两种方法,可以单独实施或组合实施以改善患者护理。

基于机构:网络将由受信任的同行组成:医疗机构或全科医生(护理人员)。对等体将运行共识协议并维护分布式分类帐。患者(或其亲属)将能够通过存储其信息的任何节点处的应用程序来访问和管理他的数据。如果对等体离线,则患者可以通过任何其他在线节点访问数据。密钥管理过程和访问控制策略将以链码编码,从而确保数据安全性和患者隐私。

特定病例(严重的医疗条件,检查,老年人护理):在患者住院治疗,康复,检查或手术期间,可以创建特定病例的分类帐。该网络将连接医生,护士和家人,以实现治疗的效率和透明度。这将有助于消除人为错误,以确保在就某一治疗阶段进行辩论时达成共识。

Scenario 2: Data Aggregation for Research Purposes. It is highly important to ensure that the sources of the data are trusted medical institutions and, therefore, the data are authentic. Using shared distributed ledger will provide tracebility and will guarantee patients’ privacy as well as the transparency of the data aggregation process. Due to the current lack of appropriate mechanisms, patients are often unwilling to participate in data sharing. Using blockchain technology within a network of researchers, biobanks, and healthcare institutions will facilitate the process of collecting patients’ data for research purposes.

Scenario 3: Connecting Different Healthcare Players for Better Patient Care.Connected health is a model for healthcare delivery that aims to maximize healthcare resources and provide opportunities for consumers to engage with caregiver and improve self-management of a health condition23. Sharing the ledger (using the permission-based approach) among entities (such as insurance companies and pharmacies) will facilitate medication and cost management for a patient, especially in case of chronic disease management. Providing pharmacies with accurately updated data about prescriptions will improve the logistics. Access to a common ledger would allow the transparency in the whole process of the treatment, from monitoring if a patient follows correctly the prescribed treatment, to facilitating communication with an insurance company regarding the costs of the treatment and medications.

Implementing the Scenarios. In order to implement the three healthcare scenarios presented above, we must choose between a permissionless and a permissioned blockchain implementations. Below we present the facts that favor a permissioned system implementation.

- The anonymity of users and impossibility to verify the identity of account holders (as in case of permissionless blockchain) could cause impersonalization and data misuse.

- Patients’ healthcare data are of high sensitive nature. Even monitoring communication between a patient and a specific clinician may reveal some sensitive data about the patient, therefore violating the privacy.

- Fast response of a system is required as any update of the information about a patient’s treatment could be crucial for the patient.

- The need to pay for transaction execution, for example, updating permissions for a medical doctor to access a piece of healthcare information or sharing some data for research could limit the usability of the system.

场景2:研究目的的数据聚合。确保数据来源是可信赖的医疗机构非常重要,因此数据是真实的。使用共享分布式分类帐将提供可跟踪性,并将保证患者的隐私以及数据聚合过程的透明度。由于目前缺乏适当的机制,患者往往不愿意参与数据共享。在研究人员,生物银行和医疗机构网络中使用区块链技术将促进收集患者数据的过程用于研究目的。

场景3:连接不同的医疗保健机构以获得更好的病人护理。互联健康是医疗保健服务的典范,旨在最大限度地提高医疗保健资源,为消费者提供与护理人员互动的机会,并改善健康状况的自我管理23。在实体(例如保险公司和药房)之间共享分类帐(使用基于许可的方法)将促进患者的药物和成本管理,尤其是在慢性疾病管理的情况下。为药房提供有关处方的准确更新数据将改善物流。获取共同分类帐将允许整个治疗过程的透明度,从监测患者是否正确遵循规定的治疗,到促进与保险公司就治疗和药物治疗的成本进行沟通。

实施方案。为了实现上述三种医疗保健方案,我们必须在无权限和允许的区块链实施之间进行选择。下面我们介绍有利于许可系统实现的事实。

用户的匿名性和验证帐户持有者身份的不可能性(如同许可区块链的情况)可能导致非个性化和数据滥用。

患者的医疗保健数据具有高度敏感性。甚至监视患者和特定临床医生之间的通信也可能揭示关于患者的一些敏感数据,因此侵犯了隐私。

需要系统的快速响应,因为关于患者治疗的信息的任何更新对于患者而言可能是至关重要的。

支付交易执行费用的需要,例如,更新医生访问医疗信息或分享一些数据用于研究的权限可能会限制系统的可用性。

3. Application in Radiation Oncology: Sharing Clinical Data between Healthcare Providers

In this section, we present a prototype design and implementation of a system to support electronic medical record sharing for primary patient care (Scenario 1). More precisely, we focus on patients that are receiving a cancer treatment via ionizing radiation, which is usually performed in the Department of Radiation Oncology of a hospital. First, we describe a specific use-case scenario and the benefits of the system. Second, we present the architecture of the system and describe the data structure and functionality of the system. Finally, we discuss how privacy, security, and scalability are ensured within the proposed framework.

3.1. Use Case Scenario

Cancer is a serious medical condition that may require a long-lasting treatment and a life-time monitoring of a patient. Therefore, it is crucial for the patient to maintain his medical history and to be able to access or share his medical data during the treatment and post-treatment monitoring. Due to the mobility of a patient, the management of the data generated during every patient’s visit can be cumbersome especially given the sensitive nature of healthcare data. How to guarantee that the patient’s data are complete, stored securely, and can be accessed only according to the patient consent in a fast and convenient manner?

We tackle this problem by applying the blockchain technology to create a prototype of an oncology-specific clinical data sharing system. To present our solution, we take as an example an oncology information system, ARIA25, which is widely used to facilitate oncology-specific comprehensive information and images management. ARIA combines radiation, medical and surgical oncology information and can assist clinicians to manage different kinds of medical data, develop oncology-specific care plans, and monitor radiation dose of patients. Different types of data stored in this system can be structured depending on the clinician’s request and exported in PDF format. The documents that contain the data such as history and physical exams, laboratory results, and delivered radiation doses are of the high importance for the clinicians and are most commonly used during the treatment.

Currently, if any of these data have to be transferred from Hospital 1 to Hospital 2, the following procedure takes place. First, the patient (or his official representative) has to sign a consent – a document that specifies the data to be transferred and contains the information about the recipient of the data (Hospital 2). Then, the information has to be printed and mailed to the recipient. Consent management and data transfer in this case can become complicated and inconvenient: the patient may need to contact the caregiver and sign a consent in the hospital from which he is not receiving care anymore. Data transfer can take time, and on receiving the hard copy of the patient data, a clinician will have to introduce them into the system again. Moreover, with this approach, it is very difficult for the patient to maintain any access control of his data and to have a complete view of the data.

By employing blockchain technology, our solution allows to facilitate the consent management and speed up data transfer. We developed a chaincode that allows a patient to easily impose fine-grained access control policy for his data and enables efficient data sharing among clinicians

3.在放射肿瘤学中的应用:在医疗保健提供者之间共享临床数据

在本节中,我们提出了一个系统的原型设计和实现,以支持初级患者护理的电子病历共享(情景1)。更确切地说,我们关注通过电离辐射接受癌症治疗的患者,这通常在医院的放射肿瘤科进行。首先,我们描述了一个特定的用例场景和系统的好处。其次,我们介绍了系统的体系结构,并描述了系统的数据结构和功能。最后,我们讨论如何在提议的框架内确保隐私,安全性和可伸缩性。

3.1。用例场景

癌症是一种严重的疾病,可能需要持久的治疗和对患者的终生监测。因此,对于患者来说,维持其病史并且能够在治疗和治疗后监测期间访问或共享他的医疗数据是至关重要的。由于患者的移动性,在每次患者就诊期间产生的数据的管理可能是麻烦的,特别是考虑到医疗保健数据的敏感性质。如何保证患者的数据完整,安全存储,并且只能根据患者的同意快速方便地访问?

我们通过应用区块链技术来创建肿瘤学特定临床数据共享系统的原型来解决这个问题。为了呈现我们的解决方案,我们以一个肿瘤学信息系统ARIA25为例,该系统被广泛用于促进肿瘤学特定的综合信息和图像管理。 ARIA结合了放射,医疗和外科肿瘤学信息,可以帮助临床医生管理不同类型的医疗数据,制定肿瘤学特定护理计划,并监测患者的放射剂量。根据临床医生的要求,可以构建存储在该系统中的不同类型的数据,并以PDF格式导出。包含历史和物理检查,实验室结果和递送辐射剂量等数据的文件对临床医生来说非常重要,并且在治疗期间最常用。

目前,如果这些数据中的任何一个必须从医院1转移到医院2,则进行以下程序。首先,患者(或其官方代表)必须签署同意书 - 指定要转移的数据的文件,并包含有关数据接收者的信息(医院2)。然后,必须打印信息并邮寄给收件人。在这种情况下,同意管理和数据传输可能变得复杂和不方便:患者可能需要联系护理人员并在他不再接受护理的医院中签署同意书。数据传输可能花费时间,并且在接收患者数据的硬拷贝时,临床医生将不得不再次将它们引入系统。此外,通过这种方法,患者很难维持对其数据的任何访问控制并且具有完整的数据视图。

通过采用区块链技术,我们的解决方案可以促进同意管理并加速数据传输。 我们开发了一种链码,使患者能够轻松地对其数据实施细粒度的访问控制策略,并在临床医生之间实现高效的数据共享

3.2. System Architecture

Figure 2 presents the architecture of our framework for the oncology-specific data management. The framework consists of the Membership service, Databases for storing healthcare data off-chain, Nodesmanaging consensus process, and APIs for different user’s roles. Currently, we focus on Doctor and Patient, but the roles and their functionality could be extended depending on the scenario.

The System Architecture of Blockchain Based Data Management and Sharing for Radiation Oncology

The main functionality of the Membership service is to register users with different roles (currently Doctor and Patient). The roles define the functionality of the chaincode that is available to the user. During the registration of a user as a Doctor, it is important to ensure that it is not a potential malicious user, but a qualified medical doctor. To verify this, the National Practitioner Data Bank could be consulted by the membership service. The membership service is also hosting a certification authority involved in the generation of a key pair for signing (SKSU, PKSU) and encryption key pair (SKεU, PKεU) for every user (U).

Patient (P) also generates a symmetric encryption key (SKAεSP) that will be used to encrypt/decrypt the data corresponding to the patient, P. This key will also be used to generate pseudonyms so that only authorized users could verify whether the ledger stores any information about the patient. When a patient (P) needs to share his data with a doctor (D), the patient could share this key, SKAεSP, using the encryption public key of the corresponding clinician (PKεD). If the symmetric key SKAεSP is compromised, the patient could generate a new one, run a proxy re-encryption algorithm26 on the data stored in the cloud and then share a new key with the clinicians according to the desired access control policy.

The patient’s data are stored off-chain in the following Databases. First, a local database management system in the hospital that stores the oncology-related data (for example, ARIA in our use case). Second, a cloud based platform (Varian Cloud) that stores patient’s data organized based on the data category (for instance, according to the sensitivity level of the data, or their semantics), and encrypted with corresponding patient key, SKAεSP. A registered clinician could assess or upload the data in the cloud repository based on the access control policy defined by the patient and implemented in the chaincode Logic.

A custom chaincode is deployed on every Node that acts as a Hyperledger validating peer. Nodes receive all transactions submitted by the users through a role-based APIs. The Node, selected as a leader, organizes transactions in a block and initiates the PBFT consensus protocol. Transactions are executed by all nodes according to the implemented chaincode Logic. The State stores the information about patients in a key-value pair format. A Key – a Patient Id in the system – is a pseudonym of the patient that is generated as a hash of the concatenation of the symmetric key SKAεSP and a Uniquely Identifiable Information of the patient (UIIp): H(SKA∈SP‖UIIP). Combination of SSN (if applicable), date of birth, given names, and a ZIP code of the patient could be used as UIIP. A Value is a patient record stored as a byte array. Next we describe the data structure in detail.

3.2。系统架构

图2显示了我们的肿瘤学特定数据管理框架的体系结构。该框架包括会员服务,用于存储离线医疗数据的数据库,管理共识流程的节点以及针对不同用户角色的API。目前,我们专注于医生和患者,但角色及其功能可以根据情景进行扩展。

图2。

基于区块链的放射肿瘤数据管理与共享系统体系结构

会员服务的主要功能是注册具有不同角色的用户(目前是医生和患者)。角色定义了用户可用的链代码的功能。在作为医生注册用户期间,重要的是确保它不是潜在的恶意用户,而是合格的医生。为了验证这一点,可以通过会员服务咨询国家从业者数据库。会员服务还托管了为每个用户(U)生成用于签名的密钥对(SKSU,PKSU)和加密密钥对(SKεU,PKεU)的证书颁发机构。

患者(P)还生成对称加密密钥(SKAεSP),该密钥将用于加密/解密对应于患者P的数据。该密钥还将用于生成假名,以便只有授权用户才能验证分类帐是否存储有关患者的任何信息。当患者(P)需要与医生(D)共享他的数据时,患者可以使用相应临床医生的加密公钥(PKεD)共享该密钥SKAεSP。如果对称密钥SKAεSP被泄露,则患者可以生成新的密钥,对存储在云中的数据运行代理重新加密算法26,然后根据期望的访问控制策略与临床医生共享新密钥。

患者的数据存储在以下数据库的外链中。首先,医院中存储肿瘤相关数据的本地数据库管理系统(例如,在我们的用例中使用ARIA)。第二,基于云的平台(Varian Cloud),其存储基于数据类别(例如,根据数据的敏感度级别或其语义)组织的患者数据,并且用相应的患者密钥SKAεSP加密。注册的临床医生可以基于由患者定义的并且在链码逻辑中实现的访问控制策略来评估或上载云存储库中的数据。

自定义链代码部署在充当Hyperledger验证对等体的每个节点上。节点接收用户通过基于角色的API提交的所有事务。被选为领导者的节点在一个区块中组织交易并启动PBFT共识协议。根据实现的链码逻辑,所有节点执行事务。 State以关键值对格式存储有关患者的信息。甲键 - 在该系统中的患者ID - 是作为对称密钥SKAεSP和患者的唯一可识别的信息(UIIP)的级联的散列产生的患者的假名:H(SKA∈SP‖UIIP) 。可以使用SSN(如果适用),出生日期,给定姓名和患者的邮政编码的组合作为UIIP。值是存储为字节数组的患者记录。接下来,我们将详细描述数据结构。

3.3. Data Structure and System Functionality

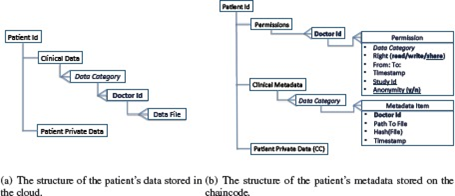

Figure 3 shows how the patient’s data and metadata are organized: the patients’ data are stored off-chain: locally (in the clinician database) and in the cloud as presented in Figure 3 (a) based on their categories. Currently we use three categories in our prototype: History and physical exams, Laboratory results, and Delivered radiation doses. In the future, we plan to define categories based on both the semantics and the sensitivity level of the data. Data files related to the patient and uploaded by different clinicians are stored within the corresponding category. A patient could optionally store some private data or notes encrypted with the patient public key, PKSP.

The data structure of a patient record

Figure 3 (b) presents the structure of the patient’s metadata that consists of the following blocks: Permissions, Clinical Metadata, and Patient Private Data (optional). Permissions block is organized as follows: every Permission corresponds to a Doctor Id, with which a clinician is registered in the system. Every permission specifies the timeframe (From: To:) during which a clinician has a Right to read the patient’s data that fall into a specific Data Category, upload them to the cloud repository (write), or share the patient’s data within a framework of a specific research study, Study Id. For the latter the patient could also use Anonymity tag to specify if the data must be anonymized before sharing or could be shared as they are. Timestamp makes every permission unique and allows a patient to update and track access control changes corresponding to the same Doctor Id.

Clinical Metadata are a block that contains information about all the data files uploaded to the cloud by different clinicians. The Metadata Items are categorized based on the semantics of the corresponding data files. Every Item contains an Id of the clinician that uploaded the data (Doctor Id), a pointer to the file that is stored in the cloud, Path to File, the Hash of the Data File, Hash(File), to ensure unforgeability of the data stored in the cloud, and the Timestamp of the event when the Data File was uploaded. Similarly to the Patient Private Data stored on the cloud, some private data could be added by a patient to be stored in the State associated with the chaincode (CC). The metadata are stored as a “value” part of a CC State. It can be accessed and modified using the functions that can be invoked on a CC.

To ensure a correct functioning of the developed chaincode we built a network that consists of a Membership service and four Nodes capable of running PBFT consensus protocol. Four is the minimum number of nodes needed to run the PBFT consensus protocol. We deployed CC on every node and issued a set of the “invoke” transactions (that trigger creation of a new patient metadata record, adding a permission, and uploading the metadata item), and “query” transactions to access the information from the State. Currently, a patient is able to create a metadata record on the chaincode, add permissions, and retrieve his up-to-date metadata record, and, thus, his data that are stored on the cloud. A user registered with a Doctor role is able to upload, access and share for research purposes the data in the cloud based on the permissions specified by the patient.

Verification of the access control rights (currently read, write or share) is done via Logic of a chaincode written in Go programming language22. For instance, every time a clinician would try to add new data on the cloud repository, a permission corresponding to this clinician has to be retrieved from the patient’s metadata record. Then, the validity of the permission with respect to the data category and timeframe is controlled. Similarly, sharing patient data for the research purposes can not be performed by clinician without patient’s agreement. This is guaranteed by the chaincode implementation. Interfacing our system with the existing clinical database management systems and conducting more experiments with the data of the real patients are next steps of our work.

3.3。数据结构和系统功能

图3显示了患者的数据和元数据是如何组织的:患者的数据存储在离线:本地(在临床医师数据库中)和云中,如图3(a)所示,基于他们的类别。目前,我们在原型中使用了三个类别:历史和物理检查,实验室结果和交付辐射剂量。将来,我们计划根据数据的语义和敏感度级别定义类别。与患者相关并由不同临床医生上传的数据文件存储在相应的类别中。患者可以选择性地存储用患者公钥PKSP加密的一些私人数据或注释。

图3。

患者记录的数据结构

图3(b)显示了患者元数据的结构,包括以下块:权限,临床元数据和患者私有数据(可选)。权限块的组织如下:每个权限对应于医生ID,临床医生在系统中注册。每个权限都指定时间范围(From:To :),在此期间,临床医生有权阅读属于特定数据类别的患者数据,将其上传到云存储库(写入),或在框架内共享患者的数据。一项特定的研究,研究ID。对于后者,患者还可以使用匿名标签来指定在共享之前数据是否必须是匿名的,或者可以按原样共享。时间戳使每个权限都是唯一的,并允许患者更新和跟踪与同一医生ID相对应的访问控制更改。

临床元数据是一个块,其中包含有关不同临床医生上传到云的所有数据文件的信息。元数据项基于相应数据文件的语义进行分类。每个项目包含上传数据的临床医生的ID(医生Id),指向存储在云中的文件的指针,文件路径,数据文件的哈希值,哈希(文件),以确保不可伪造性存储在云中的数据,以及上载数据文件时事件的时间戳。与存储在云上的患者私人数据类似,患者可以添加一些私人数据以存储在与链码(CC)相关联的状态中。元数据存储为CC状态的“值”部分。可以使用可在CC上调用的函数来访问和修改它。

为了确保开发的链代码的正确运行,我们构建了一个由成员服务和四个能够运行PBFT共识协议的节点组成的网络。四是运行PBFT共识协议所需的最小节点数。我们在每个节点上部署了CC,并发布了一组“调用”事务(触发创建新的患者元数据记录,添加权限,上传元数据项),以及“查询”事务以访问来自州的信息。目前,患者能够在链码上创建元数据记录,添加权限,并检索他的最新元数据记录,从而检索存储在云上的数据。注册了Doctor角色的用户能够基于患者指定的权限上载,访问和共享用于研究目的的云中的数据。

访问控制权限(当前读取,写入或共享)的验证是通过以Go编程语言22编写的链码的逻辑来完成的。例如,每当临床医生尝试在云存储库上添加新数据时,必须从患者的元数据记录中检索对应于该临床医生的许可。然后,控制关于数据类别和时间帧的许可的有效性。同样,未经患者同意,临床医生无法为研究目的共享患者数据。链码实现保证了这一点。我们的系统与现有的临床数据库管理系统接口,并对真实患者的数据进行更多实验是我们工作的下一步。

4. Discussion

Next we discuss the privacy, security, and scalability of the proposed framework.

Privacy. A patient’s privacy is ensured by providing the patient with a possibility to specify fine-grained access control over his data via permissions. Permissions are enforced by chaincode logic and, therefore, can not be violated by any user, unless the consensus protocols fails. The latter could happen only if a fraction of the verifying nodes intentionally tries to damage network operations. Centralized membership service already protects against Sybil attacks. Moreover, in the permissioned network, the nodes identities are known, therefore, there is no incentive for malicious behavior. In the case if a node still behaves maliciously, access to the network could be promptly restricted for this node.

Membership service also controls the identity of the users. Before registering a clinician, his identity is verified in the National Practitioner Data Bank. A patient is registered with his UII, but all his data are linked to the pseudonym generated using his secret key, SKAεSP. Therefore, Membership service does not have an access to the patient’s clinical data, yet guarantees authenticity of the users (via digital signature verification). If SKaesP is compromised or lost, access to the network will be recovered using UII of a patient, a new key will be generated, and proxy reencryption26 will be used.

Security. Clinical data stored in the cloud repository are encrypted with a patient secret key, SKAεSP to provide data confidentiality. Only the patient can share encryption key and set up the access control policy via permissions. Shared data from the cloud registry are hashed and signed with a secret key of a user (SKSU), before the data are uploaded. The hashes are stored as a part of a corresponding metadata item in the State. Transactions are also digitally signed, thus the data integrity is ensured.

Availability of the shared data is guaranteed by providing a cloud platform to store the data. Role-based APIs can be used at any node registered in the network to invoke or query the chaincode. As already mentioned, if a patient loses his credentials, access to the data stored on- and off-chain could still be recovered.

Scalability. Clinical data sharing requires scalability of the system in terms of both the number of users and the number of nodes. PBFT consensus protocol provides excellent scalability in terms of the number of users, but have not been well explored in terms of the number of Nodes (verified only up to few tens of Nodes)14. Possible scalability issues could be addressed by using hierarchical BFT protocols. Frequency of creating a block or number of transactions in a block (batch size) could be adjusted. System load is already minimized by storing patient’s clinical records off-chain. We plan to evaluate the system performance and scalability in clinical settings in future work.

4。讨论

接下来,我们将讨论所提议框架的隐私性,安全性和可扩展性。

隐私。通过为患者提供通过许可指定对其数据的细粒度访问控制的可能性来确保患者的隐私。权限由链代码逻辑强制执行,因此,除非共识协议失败,否则任何用户都不能违反这些权限。后者只有在验证节点的一小部分故意试图破坏网络操作时才会发生。集中成员服务已经可以防止Sybil攻击。此外,在许可网络中,节点标识是已知的,因此,没有对恶意行为的激励。在节点仍然恶意行为的情况下,可以立即限制对该节点的网络访问。

成员资格服务还控制用户的身份。在注册临床医生之前,他的身份在国家从业者数据库中得到验证。患者在他的UII注册,但他的所有数据都与使用他的秘密密钥SKAεSP生成的假名相关联。因此,会员服务无法访问患者的临床数据,但保证了用户的真实性(通过数字签名验证)。如果SKaesP被泄露或丢失,将使用患者的UII恢复对网络的访问,将生成新密钥,并且将使用代理重新加密26。

安全。存储在云存储库中的临床数据使用患者密钥SKAεSP加密,以提供数据机密性。只有患者可以共享加密密钥并通过权限设置访问控制策略。在上载数据之前,来自云注册表的共享数据被散列并使用用户的密钥(SKSU)进行签名。散列存储为状态中对应元数据项的一部分。事务也经过数字签名,因此确保了数据的完整性。

通过提供用于存储数据的云平台来保证共享数据的可用性。可以在网络中注册的任何节点上使用基于角色的API来调用或查询链代码。如前所述,如果患者丢失其凭证,则仍可以恢复对存储在链上和链外的数据的访问。

可扩展性。临床数据共享需要系统在用户数量和节点数量方面的可扩展性。 PBFT共识协议在用户数量方面提供了出色的可扩展性,但在节点数量方面尚未得到很好的探索(仅验证了几十个节点)14。可以通过使用分层BFT协议来解决可能的可伸缩性问题。可以调整在块(批量大小)中创建块或事务数的频率。通过将患者的临床记录存储在链外,已经最小化了系统负荷。我们计划在未来的工作中评估临床环境中的系统性能和可扩展性。

5. Related Work

The potential of the applications built on top of the blockchain technology for healthcare data management has been recently discussed7, 27–29. Yue et al. claim to be the first to import blockchain into the design of a healthcare system27. They presented the architecture of a healthcare data gateway application for easy and secure control and sharing of medical data between different entities that may use patient data. However, the system has not been implemented nor tested yet. A possibility of sharing the data for research purposes is only sketched in the paper, without any security or privacy evaluation. Jenkins et al. proposed to use blockchain technology for a multifactor authentication in a specific research scenario (medical large data analysis with functional biomarkers) that involves biometric and biomedical data28.

MedRec7 is the first and the only functioning prototype that have been proposed until now. The authors presented a system based on Ethereum smart contracts for an intelligent representations of existing medical records that are stored within individual nodes on the network. Two incentivizing models for “mining” are also proposed in7. Our prototype significantly differs from the framework in7. First, MedRec is based on permissionless blockchain implementation and PoW, thus involves transaction fees, and requires involvement into “mining” and account management processes. In contrast, we have chosen permissioned blockchain implementation based on the requirements from the medical perspective. We justified our choice in Section 3.4. Second, in7 the patients data are stored locally at every node. We decided to use a cloud-based storage, and employ encryption and key-sharing to ensure availability of the data even if the hospital node is temporary off-line.

5.相关工作

最近讨论了基于区块链技术建立在医疗保健数据管理之上的应用程序的潜力7,27-29。岳等人。自称是第一个将区块链导入医疗保健系统27的设计。他们介绍了医疗数据网关应用程序的体系结构,以便在可能使用患者数据的不同实体之间轻松安全地控制和共享医疗数据。但是,该系统尚未实施或测试。为了研究目的而共享数据的可能性仅在文章中概述,没有任何安全性或隐私评估。詹金斯等人。建议在特定的研究场景(使用功能生物标记的医学大数据分析)中使用区块链技术进行多因素认证,其涉及生物识别和生物医学数据28。

MedRec7是迄今为止提出的第一个也是唯一一个有效的原型。作者提出了一个基于以太坊智能合约的系统,用于存储在网络上各个节点内的现有医疗记录的智能表示。还提出了两种用于“采矿”的激励模型。我们的原型与7中的框架明显不同。首先,MedRec基于无权的区块链实施和PoW,因此涉及交易费用,并且需要参与“挖掘”和账户管理过程。相比之下,我们根据医学角度的要求选择了允许的区块链实施。我们在3.4节中证明了我们的选择。其次,患者数据在每个节点本地存储。我们决定使用基于云的存储,并采用加密和密钥共享来确保数据的可用性,即使医院节点是临时离线的。

6. Conclusion and Future Work

In this paper, we proposed scenarios of blockchain technology application in different healthcare settings: primary care, medical data research, and connected health. We discussed how maintaining an immutable and transparent ledger, which keeps track of all the events happened across the network, could improve and facilitate the management of medical data.

Based on the constrains related to the healthcare context, we justified the choice of the permissioned blockchain technology for the implementation of the proposed scenarios. We also presented an architecture of the framework for the specific needs in case of radiation oncology data sharing and implemented a prototype that ensures privacy, security, availability, and fine-grained access control over highly sensitive patients’ data.

As part of future work, we would like to extend the structure of a patient record and its metadata, using the semantics of healthcare data, including the possibility of sharing radiology images, which is much more challenging. Since we work in collaboration with a hospital, we plan to test our system with the data of the real patients. Our long term goal is to explore other scenarios proposed in the paper (such as connected health and medical data research) and apply them in practice to enhance the current healthcare data management.

6.结论和未来工作

在本文中,我们提出了区块链技术在不同医疗环境中的应用场景:初级保健,医学数据研究和互联健康。我们讨论了如何维护一个不可变且透明的分类账,它可以跟踪网络中发生的所有事件,可以改善和促进医疗数据的管理。

与医疗保健背景相关的约束,我们证明了为实施所提议方案而选择的许可区块链技术。我们还针对辐射肿瘤学数据共享的具体需求提出了框架架构,并实施了一个原型,确保对高度敏感的患者数据的隐私,安全性,可用性和细粒度访问控制。

作为未来工作的一部分,我们希望使用医疗数据的语义扩展患者记录及其元数据的结构,包括共享放射图像的可能性,这更具挑战性。由于我们与医院合作,我们计划用真实患者的数据测试我们的系统。我们的长期目标是探索本文提出的其他方案(例如关联的健康和医疗数据研究),并将其应用于实践中,以加强当前的医疗数据管理。

References

1. The HIPAA Privacy Rule [Internet] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2017. [cited 9 March 2017]. Available fromml:http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/

2. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21 Food and Drugs. Department of Health and Human Services. Part 50: Protection of human subjects [Internet] 2017. [cited 1 July 2017]. Available fromml: https://www.ecfr.gov/

3. Code of federal regulations. Title 45 Public welfare. Part 46: Protection of human subjects [Internet] US Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [cited 9 July 2017]. Department of Health and Human Services. Available fromml: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/[Google Scholar]

4. EU Directive. 95/46/ec of the european parliament and of the council of 24 october 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. Official Journal of the EC. 1995;23(6) [Google Scholar]

5. An update on Google Health and Google PowerMeter [Internet] Google official blog. 2017. [cited 9 March 2017]. Available fromml:https://googleblog.blogspot.ch/2011/06/update-on-google-health-and-google.html.

6. Nakamoto S. Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. 2008 [Internet]. Available fromml: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. Azaria A, Ekblaw A, Vieira T, Lippman A. Medrec: Using blockchain for medical data access and permission management. In 2016 2nd International Conference on Open and Big Data (OBD) 2016 Aug;:25–30. [Google Scholar]

8. White paper. Ethereumml: A next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform. 2014. [Internet]. Ethereum. [cited 9 March 2017]. Available fromml: github.com/ethereum/wiki/wiki/White-Paper.

9. Buterin V. On Public and Private Blockchains. [cited 9 March 2017];[Internet]. Ethereum blog. 2015 Available fromml: https://blog.ethereum.org/2015/08/07/on-public-and-private-blockchains/ [Google Scholar]

10. Cachin C. Architecture of the hyperledger blockchain fabric. [Internet] 2016. Available fromml: https://www.zurich.ibm.com/dccl/papers/cachin_dccl.pdf.

11. Hyperledger White paper [Internet] Hyperledger Project. [cited 9 March 2017]. Available fromml: https://github.com/hyperledger/

12. Ethereum Homestead Documentation [Internet] [cited 9 March 2017]. Available fromml: http://www.ethdocs.org/en/latest/

13. Gervais A, Karame GO, Wst K, Glykantzis V, Ritzdorf H, Capkun S. On the security and performance of proof of work blockchains [Google Scholar]

14. Vukolić M. In International Workshop on Open Problems in Network Security. Springer; 2015. The quest for scalable blockchain fabric: Proof-of-work vs. bft replication; pp. 112–125. [Google Scholar]

15. O’Dwyer KJ, Malone D. Bitcoin mining and its energy footprint. In Irish Signals & Systems Conference 2014 and 2014 China-Ireland International Conference on Information and Communications Technologies (ISSC 2014/CIICT 2014). 25th IET; IET. 2013. pp. 280–285. [Google Scholar]

16. QuantumMechanic. Proof of stake instead of proof of work, 2011. [Internet]. Bitcoin forum. [cited 9 March 2017]. Available fromml: bitcointalk.org.

17. Stewart I. Proof of burn, 2012. [cited 9 March 2017];[Internet]. Bitcoin Wiki.Available fromml: bitcoin.it. [Google Scholar]

18. Bonneau J, Miller A, Clark J, Narayanan A, Kroll JA, Felten EW. In IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. IEEE; 2015. Sok: Research perspectives and challenges for bitcoin and cryptocurrencies; pp. 104–121. [Google Scholar]

19. Castro M, Liskov B. Practical byzantine fault tolerance and proactive recovery. ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS) 2002;20(4):398–461.[Google Scholar]

20. Swanson T. Consensus-as-a-service: a brief report on the emergence of permissioned, distributed ledger systems. 2015 [Google Scholar]

21. GEM [Internet] Available fromml: https://gem.co/health/

22. The Go Programming Language [Internet] Available fromml:https://golang.org.

23. Connected health [Internet] Available fromml: https://en.wikipedia.org/

24. Hyperledger Fabric [Internet] [cited 9 March 2017]. Available fromml:https://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io.

25. ARIA Oncology Information System [Internet] Varian Medical Systems.[cited 9 March 2017]. Available fromml:https://www.varian.com/oncology/products/software/information-systems/aria-ois-radiation-oncology.

26. Ateniese G, Fu K, Green M, Hohenberger S. Improved proxy re-encryption schemes with applications to secure distributed storage. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2006;9(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

27. Yue X, Wang H, Jin D, Li M, Jiang W. Healthcare data gateways: Found healthcare intelligence on blockchain with novel privacy risk control. Journal of Medical Systems. 2016;40(10):218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Jenkins J, Kopf J, Tran BQ, Frenchi C, Szu H. In SPIE Sensing Technology+Applications. International Society for Optics and Photonics; 2015. Bio-mining for biomarkers with a multi-resolution block chain; pp. 94960N–94960N. [Google Scholar]

29. Beninger P, Ibara MA. Pharmacovigilance and biomedical informatics: a model for future development. Clinical Therapeutics. 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Zyskind G, Nathan O, Pentland A. Enigma: Decentralized computation platform with guaranteed privacy. arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.03471. 2015[Google Scholar]

31. Baig MM, Li J, Liu J, Wang H. Cloning for privacy protection in multiple independent data publications. Proceedings of the 20th ACM international conference on Information and knowledge management - CIKM’11. 2011:885.[Google Scholar]

32. Dubovitskaya A, Urovi V, Vasirani M, Aberer K, Schumacher MI. In IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, SEC 2015. Springer Science and Business Media; 2015. A cloud-based ehealth architecture for privacy preserving data integration. [Google Scholar]

33. Moore C, O’Neill M, O’Sullivan E, Doroz Y, Sunar B. Practical homomorphic encryption: A survey. 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS) :2792–2795. [Google Scholar]

参考

1. HIPAA隐私规则[互联网]美国卫生与公众服务部。 2017. [引用2017年3月9日]。可从以下网址获得:http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/

2.联邦法规。标题21食品和药品。卫生与人类服务部。第50部分:保护人类受试者[互联网] 2017年。[引自2017年7月1日]。可从以下网址获取:https://www.ecfr.gov/

3.联邦法规。标题45公共福利。第46部分:保护人体[互联网]美国卫生与公众服务部; 2009年。[引用2017年7月9日]。卫生与人类服务部。可从以下网址获取:https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/ [Google学术搜索]

4.欧盟指令。 1995年10月24日欧洲议会和理事会关于个人数据处理和此类数据自由流动的个人保护的第95/46 / ec号决定。欧盟官方期刊。 1995; 23(6)[Google学术搜索]

5. Google Health和Google PowerMeter [互联网] Google官方博客的最新动态。 2017. [引用2017年3月9日]。可从以下地址获得:https://googleblog.blogspot.ch/2011/06/update-on-google-health-and-google.html。

6. Nakamoto S.比特币:点对点电子现金系统。 2008 [互联网]。可从以下网址获得:https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf。 [谷歌学术]

7. Azaria A,Ekblaw A,Vieira T,Lippman A. Medrec:使用区块链进行医疗数据访问和权限管理。 2016年第二届开放和大数据国际会议(OBD)2016年8月; 25-30。 [谷歌学术]

8.白皮书。以太坊:下一代智能合约和分散式应用平台。 2014. [互联网]。复仇军。 [引用2017年3月9日]。可从以下版本获得:github.com/ethereum/wiki/wiki/White-Paper。

9. Buterin V.关于公共和私人区块链。 [引用2017年3月9日]; [互联网]。以太坊博客。 2015可从以下网站获取:https://blog.ethereum.org/2015/08/07/on-public-and-private-blockchains/ [Google Scholar]

10. Cachin C.超边框区块链结构的架构。 [互联网] 2016年。可从以下网址获取:https://www.zurich.ibm.com/dccl/papers/cachin_dccl.pdf。

11. Hyperledger白皮书[互联网] Hyperledger项目。 [引用2017年3月9日]。可从以下网址获得:https://github.com/hyperledger/

12.以太坊宅基地文献[互联网] [引自2017年3月9日]。可从以下网址获得:http://www.ethdocs.org/en/latest/

13. Gervais A,Karame GO,Wst K,Glykantzis V,Ritzdorf H,Capkun S.关于工作区块链证明的安全性和性能[谷歌学者]

14.VukolićM。在网络安全开放问题国际研讨会上。斯普林格; 2015.对可扩展区块链结构的追求:工作证明与bft复制;第112-125页。 [谷歌学术]

15. O'Dwyer KJ,Malone D.比特币采矿及其能源足迹。 2014年和2014年爱尔兰信号与系统会议中国 - 爱尔兰信息通信技术国际会议(ISSC 2014 / CIICT 2014)。第25届IET; IET。 2013.第280-285页。 [谷歌学术]

16. QuantumMechanic。工作证明而不是工作证明,2011年。[互联网]。比特币论坛。 [引用2017年3月9日]。可从以下版本获得:bitcointalk.org。

17. Stewart I.烧伤证明,2012年。[引用2017年3月9日]; [互联网]。比特币维基。可用fromml:bitcoin.it。 [谷歌学术]

18. Bonneau J,Miller A,Clark J,Narayanan A,Kroll JA,Felten EW。在IEEE安全和隐私研讨会上。 IEEE; 2015. Sok:比特币和加密货币的研究视角和挑战;第104-121页。 [谷歌学术]

19. Castro M,Liskov B.实际的拜占庭容错和主动恢复。 ACM Transactions on Computer Systems(TOCS)2002; 20(4):398-461。 [谷歌学术]

20. Swanson T.共识即服务:关于许可分布式分类账系统出现的简要报告。 2015 [谷歌学者]

21.创业板[互联网]可从以下网站获取:https://gem.co/health/

22. Go编程语言[Internet]可从ml:https://golang.org获得。

23.互联健康[互联网]可从以下网址获取:https://en.wikipedia.org/

24. Hyperledger Fabric [互联网] [引自2017年3月9日]。可从以下版本获得:https://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io。

25. ARIA肿瘤学信息系统[互联网]瓦里安医疗系统。 [引用2017年3月9日]。可从以下网址获得:https://www.varian.com/oncology/products/software/information-systems/aria-ois-radiation-oncology。

26. Ateniese G,Fu K,Green M,Hohenberger S.改进了代理重加密方案,其应用程序用于保护分布式存储。 ACM Trans。天道酬勤。 SYST。 SECUR。 2006; 9(1):1-30。 [谷歌学术]

27. Yue X,Wang H,Jin D,Li M,Jiang W.医疗保健数据网关:通过新颖的隐私风险控制找到区块链的医疗情报。医学系统杂志。 2016; 40(10):218。 [PubMed] [Google学术搜索]

28. Jenkins J,Kopf J,Tran BQ,Frenchi C,Szu H. In SPIE Sensing Technology + Applications。国际光学与光子学会; 2015.具有多分辨率嵌段链的生物标记物的生物采矿; pp.94960N-94960N